In Conversation with Oussama Tabti

In this interview, Borbála Magdolna Pál sits in conversation with Algerian artist Oussama Tabti during the Neighbouring Frequencies exhibition at the De Brakke Grond Amsterdam. Tabti delves into the materiality of his practice, the opportunities he sees in that and how one may be able to imagine beyond difference.

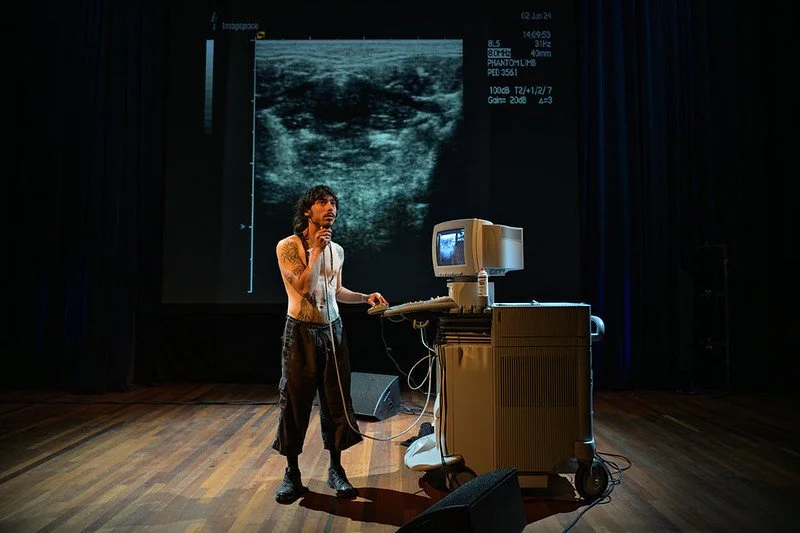

“Homo-carduelis” at de Brakke Grond. Neighbouring Frequencies, FIBER Festival 2024. Photo credit: Pieter Kers

Borbála Magdolna Pal: Hey, how are you? How are you finding FIBER?

Oussama Tabti: Hey, I am doing well. It is a sound festival, so that is super interesting because I mostly use low-tech stuff.

Is it the tangibility of low-tech that catches your attention?

Well, for instance in this installation, “Homo-carduelis” I used bird cages which I got at the flea market but the device that makes the installation work is pretty high-tech in terms of the speakers and media players. So I use the objects that I notice in my daily life, I am more interested in those.

The other project (“Parlophone”) that I exhibited in De Brakke Grond last year was the doorbells, and when you ring them you can hear the stories of someone. So the doorbells are specific to Brussels, there is the original doorbell and then there are many others that are added when new people come, almost like an archive of people who have lived in the house– a residue. There is a constant play between something that is still working and something that is archeologic. I like the patina you get from retrieving things that are abandoned or about to be destroyed. You feel that there is a story behind this, and the objects have many lives.

What I found when looking at your larger body of works, including the bird cages which you are currently exhibiting, is that your work revolves around systems and networks where things interact with one another but also encircle themselves. Regarding the notion of hermetic geopolitics, I was wondering if anything has changed since publishing that text in 2017.

No, it's still right, it is still about geopolitics. Especially now, although I said ‘especially now’ six years ago. You know, I was born in Algiers and the same year there was a series of protests (a prelude to what the Arab Spring would look like almost) and around 600 people died and then a few years after that the civil happened for about 10 years which we call the ‘Black Decade.’ So my childhood was in the middle of all of that and we can see the repercussions of all of that in everyday life when you're there. My first time at art school too I was studying graphic design and I learnt how to observe and how to express an idea simply. Then my work started to become about observations.

My first artwork was books that I took from the Institut Francais. There was a library which I would go to and then I noticed that on the last pages of the books, there were yellow post-its with stamps that corresponded with the dates of the Black Decade and from 1994-1999 the Institut was closed so there were no stamps. I took it as a testimony of that period. From there I always try to talk about things and the human but without showing the human. I like to talk about what the human did, what the human left behind but without necessarily having them be present as an image. Since then everything has been related. The colonisation, the Civil War, the emigration to Europe. History is a chain. That is why the geopolitics is perfect.

So what about it makes it hermetic? In a way, geopolitics is a network of systems, yet some people cannot access this, and cannot access the globalised network. What about it makes it geopolitics, plural and not just a geopolitic?

I do not think that there are different geopolitics, we all belong to one but through different angles, through the same shit [laughs]. I also feel that ever since moving to Europe I still talk about the same topics—the work I did in Algiers is maybe different to the work I am doing now formally—but it is linked thematically. Since it is my work but if I move to Colombia tomorrow, then sure the work will change but I am looking for things where I recognise myself.

Yeah, I saw that within the larger body of your work, it is stubbornly coherent almost. Regarding “Homo-carduelis”, what is the difference between a border and a cage?

A cage is a border and a border is a cage, maybe invisible but it is a cage. When you live in a country where you need a visa for everything you feel like you are in a cage. There is no normal, there is no escape. They are the same thing.

Are there different types of cages then?

Of course. I feel like human beings are extraordinary, they can achieve so many things– be smart, and live in symbiosis with nature—but we are living in an era where we are limited by so many things like capitalism, the geopolitics, the religions, the cultures. We are not totally independent or autonomous. The human being used to make its own food before hunting and maybe there will come a time when a generation does not know how strawberries are cultivated, or they cannot name a fruit.

I am impressed by the goldfinch firstly because it is part of my culture as we have it as a pet but held in captivity. So there is already this complex relation but the Latin, scientific name of the goldfinch is Carduelis carduelis, which comes from Carduus which is the thistle, the spikey plant. The goldfinch is incredible because nature made them able to eat from this spikey and really difficult plant and in this difficult context the human being decided to put him in a cage and give them a small quantity of food. That is my first idea about the installation, we can have more but this was my initial starting point.

Oussama Tabti and “Homo-carduelis”.

How do you feel then moving to Europe and working as an artist?

I did not have a problem myself. I did graphic design in Algiers because I thought it was safe but then I was disappointed by design because of the lack of creative freedom. So I started to do my artistic work, and then when I wanted to study art I moved to Aix-en-Provence in the South of France where I did two years. So, I did not face issues. I could take what I wanted to take.

Nevertheless, the piece Parlophone came out of my own experience. I had a French visa which I thought I could exchange with just a Belgian one but I had to start from the beginning, going to the Belgian embassy in France in Paris asking for a Belgian visa and wait. So I did that and then they ask you to have a doorbell as the first thing. Like, once they have your application they send a policeman to your house to check if you really live at the address that you are registered at.

It is really interesting that the first thing that you have to do when moving to a new country is making sure the government can call upon you in your private residence.

Yeah, I also found it strange. When I moved to Brussels I used to live in an apartment which was owned by my friends. In any case, I did not have space to put up a doorbell so I bought a wireless doorbell and I fixed it on the wall with my name on it. That is when I understood why all the people have the same thing with the wireless doorbells. It can look like a sculpture, sometimes it is really beautiful and when you get closer you can see the names of all the people but you realise that they come from all over the world yet they are living in the same building. However, those people are not only names, nationalities or doorbells, they also have stories so I started to collect them. The reason I am saying that is because it starts from a personal event. Some have asked me why I do not say my story but it is already there. In each story, there is a detail that could be mine and I recorded thirty-three people.

In this sense what is the role of the viewer? And now that you are working with sound again, in the context of FIBER, what happens when the viewer becomes a listener?

You know we all have different ways of looking or hearing a work. It is not something that I can control. Well, I think sound can be more impressive sometimes. I use low-tech materials so there is this element of it being underwhelming when looking at the object itself while you also want to touch it, you cannot say that it is too sophisticated, or too fancy. The viewer also becomes a part of the network of the art, although I do not think there is much difference between a viewer and a listener in terms of their attention. Some people become an audience for a minute and some stick around longer.

What I am curious about is that there is such a rich visual semiotics of politics and we are so used to seeing symbols and images but does the geopolitics have a sound? I mean this is why I was so drawn to the work of Homo-carduelis: the cages are effectively empty but still produce the sound of the birds because of the speaker which anthropomorphically almost becomes them.

What we hear in the cages is still effectively goldfinch chirping but imitated. I collaborated with two guys who imitate birds as their main occupation. For the moment, I have never only used sound and there is always a form that diffuses sound. In the beginning, it has an aspect of sculpture or installation and each time I think about sound work it comes from something. So it has a sculptural aspect in the beginning but after an interaction, there may be sound so the viewer and listener again remain the same, unless they do not want to engage in some parts of the work. I try and find subjects and make them into ideas, how people perceive that I cannot and do not want to control [laughs]. You are always free to understand differently.

I do not know if geopolitics has a sound but there is something about recording. Few years ago I did a work about immigrant workers from the Maghreb region who moved to France in the 60s, 70s and 80s. I started to do a lot of research about them, looking at films, documents, and photographs. For most, I felt that the people who collected this material (like the photographs and videos) just went there and started to record and I did not like it. It was awkward actually. So for me, if the research and taking records take time, it takes time. In some way that has become a part of my practice: I do not want to film you, I do not want to show you but I want to speak about your case. And I like this idea that if you cannot fully see then the listener and viewer can imagine what the person on the other end of the artwork looks like and you realise that it could be about anyone around you. Everything and everyone can be a witness to something and that is an idea that I like to think with.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.