“Second Breath”:

Adventures in the Posthuman Swamp

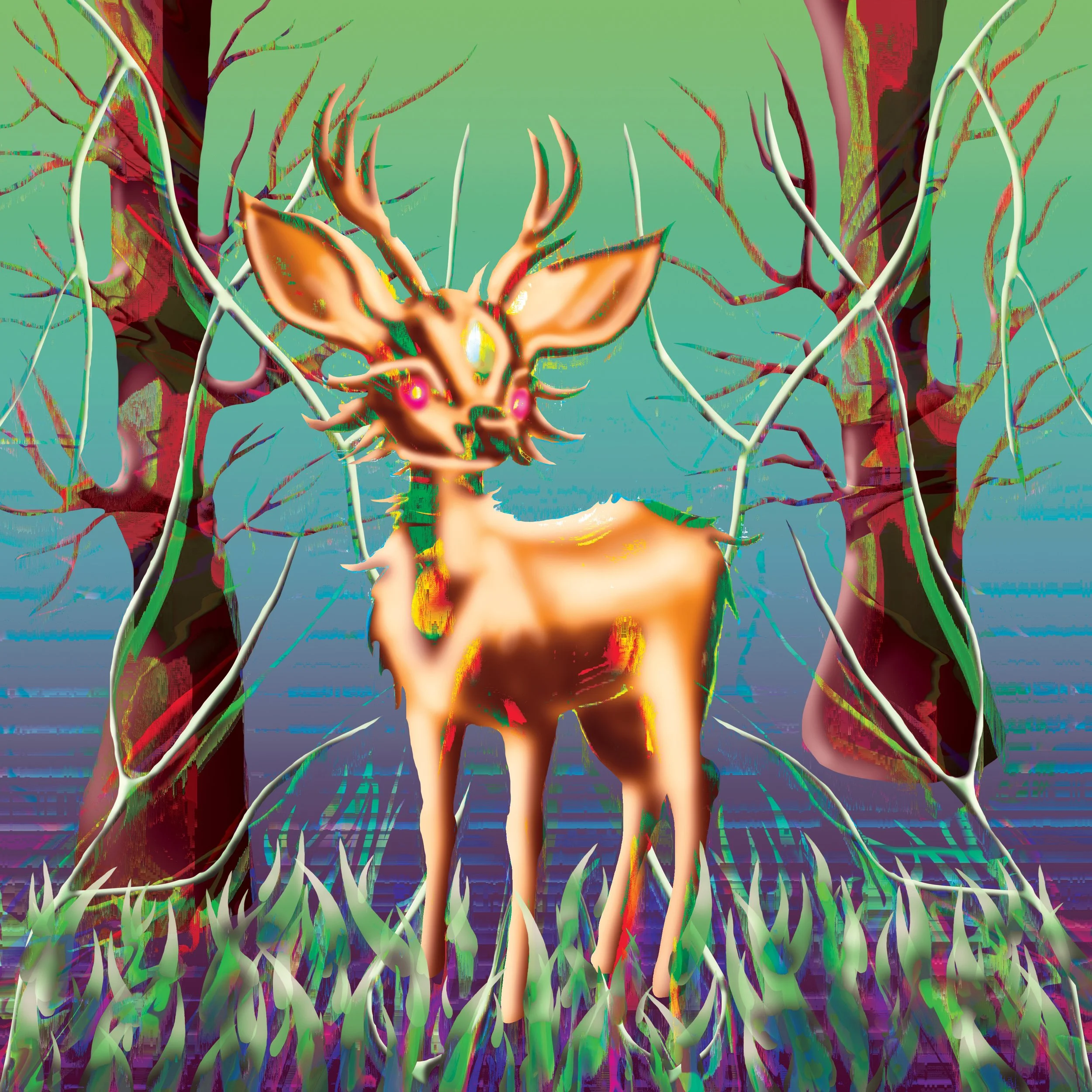

Inspired by the fascinating anatomy of frogs, Myra-Ida van der Veen’s performance Second Breath transports us to a posthuman swamp. Who’s there?

Second Breath at FIBER Festival. Photo redit: Alex Heuvink

The light dims to complete black. A room full of people breathes, waits. Then a sound from the back of the room, tender, not-quite-human, and an answer closer by. With each note, a warm light flickers on, grows, illuminates the outlines of a face, breath caught like a firefly in a jar. Three voices now, mingling; three lights, growing and receding, conversing across the undefined dark space we share. They create a rhythm we can’t quite anticipate — where will the next call come from, the next glimpse of light?

“Inspired by the fascinating anatomy of frogs”, the description had read, and I found myself transported to a posthuman swamp. Who’s there?

A few days later, with the light back on and the magic somewhat diluted, I spoke to the artist and instrument-maker Myra-Ida van der Veen over the phone. “What is your research process like when you make a new work like Second Breath?” Myra-Ida explained that the process reaches back years: “When I started studying Art-Science in The Hague, I already had the idea to make instruments for choir with electronics, because it was something that I didn't see yet so often, and I actually just wanted to see it. The voice is a fragile instrument, it's so related to your own body. In my practice, technology always involved a computer, some data and live vocal processes, which somehow always felt a bit unnatural to me.” This gap was bridged when she encountered a video of frogs calling out to each other: “I started researching this evolution that they went through. They developed bigger throats that can expand to become louder, and amplify certain frequencies to find their mates.”Many frog species evolved to have these so-called vocal sacs, whereas older species continue to live without it. “It also works as a noise cancelling device, amplifying certain frequencies but cancelling out others, so the frog can really hear its own species better.”, Myra-Ida continued. “Then I found out that people who have hearing problems sometimes use balloons on their cheeks when they go to a concert, so they can feel the music’s vibrations. So it clicked for me that there is a relation between balloons and amplifying frequencies. I thought this is interesting for a choir: getting inspired and applying the natural evolution of frogs to our own bodies, and how we perceive our voice in this world that is very loud. There’s so much sound pollution—how could we adapt our voices to that?” Frog calling. Credit: Ady Krisanto on Wikimedia

When is it ever really dark in a city? When is it ever really quiet? Often, while waiting at a traffic light with my bike in the scorching sun or pouring rain, enduring the loud rush of cars and inhaling their fumes, I wonder why we are so used to polluting each other’s senses and bodies.

“One of the most striking aspects of the performance, to me, was that it was really dark in the room. So I wanted to ask: how do you work with darkness?” “I think for me, darkness is really important.”, Myra-Ida told me. “From the audience’s perspective, it might give this feeling of childlike wonder. It’s a bit scary, it makes you listen more—for me seeing this small light in the darkness is a cosy feeling, it reminds me of sitting around a fireplace outside, which can create togetherness between people.” She moved to the performer’s perspective: “I like to sing together with people in darkness, because it makes you more free in how you move while you sing, when only your voice exists. You're less aware of how your body looks from the outside, it's more about what's happening on the inside.” Audience and performers might share this feeling: “You kind of forget that there's an outside, because there's only this one light in the darkness and nothing around it matters. I think it’s maybe easier for people to go inwards and be touched by what's happening inside of them, because it's dark.” Why are we so used to polluting each others’ senses and bodies? One possible answer is that the cities we inhabit were designed by and for people who understood themselves as bounded individuals, and who believed their faculty for reason resided inside their similarly contained minds. As a bounded individual, your skin is a barrier, a shield, you function independently of what goes on around you: an autopoietic system. Like the frogs, you filter out frequencies that don’t pertain to you.

Following this logic, the exhaust from internal combustion engines does not enter deeper than your skin, and since reason resides in your mind, it cannot be impacted by adverse weather conditions and noise. What is important to you, first and foremost, is your own individual freedom, so you design infrastructures customised to you, which move you around as you please. You build a world you can navigate through sight and sound, and barely notice as taste, touch and smell gradually fade away.

“You also work with scent sometimes, right? In what ways?”“I mostly work with it for my band, INNERUU. We always have lots of fresh grass scents in the space, because we have gigs in very different sight specific locations.“ Smelling fresh grass is what makes their performances instantly recognisable, and memorable: “When people leave or return, they remember the scent, so you can play with the memory of this performance. We also sell the scent as merch, so you can take a little bit of the experience home with you. It’s about how to extend the performance through time, through smell.”inneruu performing. Credit: artist’s website, used with permission

Today, the logic of bounded individualism is no longer viable. In the poignant words of Science and Technology scholar Donna Haraway: “Bounded (or neoliberal) individualism amended by autopoiesis is not good enough figurally or scientifically; it misleads us down deadly paths.” What other frequencies could we tune into, theory-wise? Who’s there in the posthuman swamp? We may notice calls from the emerging fields of new materialism and material feminism, reminding us that our bodies don’t strictly begin or end at the skin. We know by now that most of the DNA we contain is not human, but microbial: We are always-already hybrids somewhere between human and other. New materialist scholar Stacy Alaimo calls this trans-corporeality: “The ‘environment,’ as we now apprehend it, runs right through us in endless waves, and if we were to watch ourselves via some ideal microscopic time-lapse video, we would see water, air, food, microbes, toxins entering our bodies as we shed, excrete, and exhale our processed materials back out”.

Second Breath makes this exhale visible. The growing light, the sound contained in a balloon — Myra-Ida shared that one of her fellow performers thinks of them as a newborn child, and of the performance as mothering the breath.Mothering the breath. Credit: artist’s website, used with permission

From such understandings of interconnectedness and care emerges a new ethics, one that “demands that we inquire about all of the substances that surround us, those for which we may be somewhat responsible, those that may harm us, those that may harm others, and those that we suspect we do not know enough about.” Such an ethic also urges us to dissolve the structures we find ourselves in: “[It] calls us to somehow find ways of navigating through the simultaneously material, economic, and cultural systems that are so harmful to the living world and yet so difficult to contest or transform.”

“You work with these hybrid beings, human-technology or human-animal hybrids. Do you ever think about what cities might look like that these kind of more-than-human figures live in?”“How can cities adapt with us if we adapt our bodies? That's a good question.”, Myra-Ida considered. “Now everything is very visual, we have a phone, we need to see where to go, all this information is processed through our eyes. Smell and all the other senses are becoming weaker because we are not really using them anymore.” She began a series of sensory speculative fabulations: “So technology went this way, but we are not questioning if that's really the way we wanted to go. Maybe there could be technology that conveys information through touch and the things we wear. Then suddenly all the signs, the visual graphic designs that we have nowadays in cities would become unnecessary, because we understand things through feeling with our skin.Or maybe we will create artificial noses and we’ll know which way to go because we can smell better. Or night vision hybrids… if we all had night vision, you don't need any street lights anymore and we wouldn't have all this light pollution.” “Cyborgs for earthly survival!”, Haraway proclaimed forty years ago. Today, she considers cyborgs to be just one part of a worming litter of critters necessary for earthly survival. The posthuman swamp is home to both laptops and lapdogs, technology aids but does not define relations of kind and care across species. Following the Anthropocene, our current self-assured but crumbling “Age of Man”, Haraway hopes for a Chthulucene: a time of tentacles, feelers, from Latin tentare, “to feel” and “to try”, a time to root earthwards through all our senses, augmented or not.

Can you tell me more about your upcoming film project, Extended Bodies? Myra-Ida explained the experimental film takes viewers into a world where breathing is the ultimate expression of human instinct. It explores the boundaries of discipline, imagination, and bodies in an ever-changing environment. In a rapidly changing world, people create ways to adapt to their surroundings. The quest for ways to extend our bodies as an evolutionary response to a changing world. This evolutionary process is shown in various ways, where breathing in each story is a primal instinct that will always remain constant. The film has three different storylines in which one is made in collaboration with Lisa Frederiks, who had written the theatre play ‘Koud lichaam’. Still from Extended Bodies. Credit: artist’s website, used with permission

Human “feelers”, in the form of infrastructure and technology, already extend across the Earth. Maybe talking to a friend across the ocean or empathising with the suffering of people on the other side of the globe through a news broadcast is not so different from frogs calling to each other through the dark across the pond. Attuning to more-than-human sensory worlds might help us reach more gently than we are used to inside the posthuman swamp. Such ecological attunement can be explored through play – with “playful care”, as philosopher Timothy Morton proposes, with “playful seriousness”, a mode of exploration that “would have a slight smile on its face, knowing that all solutions are flawed in some way.”

“How do you incorporate play in your work?” “Playing and playfulness, it is quite important to me in the making process or for getting to ideas.”, Myra-Ida reflected. “Exploring different materials, different sounds and ways of moving through the space create this childlike wonder. If you want to make something as a group, I think it's very important to be playful together, try not to judge what you are doing and just do it. Most of the time, if you enter this kind of state as a group, beautiful things emerge from it.”How do we navigate through our current infrastructural, cultural and economic systems, “so harmful to the living world and yet so difficult to contest or transform”? One way is through artistic practices like Myra-Ida’s, tentatively, tentacularly: to feel, to try. And through telling stories this way: subtle, sensory stories that open just enough imaginary space to wedge a foot, or paw, or claw in the door of these systems. In this way, art opens up space for different futures: “The artwork is a sort of gate through which you can glimpse the unconditioned futurality that is a possibility condition for predictable futures”, writes Timothy Morton. “Art is maybe one tiny corner in our highly (too highly) consciously designed—and way too utilitarian—social space where we allow things to do that to us.

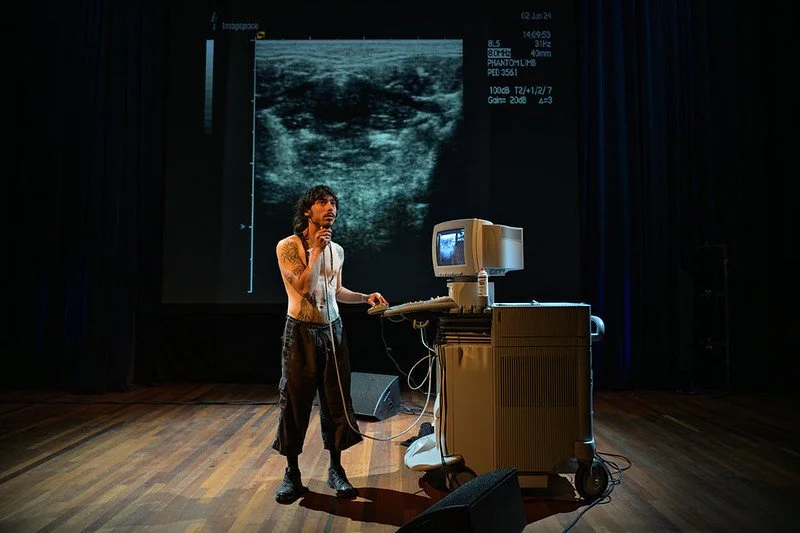

Performance of Elek by Myra-Ida van der Veen. Credit: artist’s website, used with permission

“What role does storytelling play in your practice?” “When I think about storytelling, especially in Second Breath, I would say that it's not so much in the foreground. For me, it’s about composing audio-visual aspects that are abstract enough to impose your own imagination on it.” What she composes, Myra-Ida told me, is the emotional story: “I compose the space, I compose the light, darkness, attention, silence and sounds. And there is this moment when it’s silent and the balloon gets blown up further and further and you don’t know how big it can get, so you compose tensions in a very abstract way.”The concrete story remains an open imaginary space for the audience to fill in: “I always get a lot of questions like: Are you trumpet players or are you frogs or are you dinosaurs or are you performers? Are you dancers? I like to keep it open, because it's not so much about that while we are making it either. All the different performers see something different in it, too. There are so many different stories and imaginations you can impose on it. And I enjoy those talks afterwards with different people who all come up with stories and share it with each other as if they share dreams after a long night's sleep. ”The light dims to complete black. We breathe and wait. The posthuman swamp comes abundantly alive with calls, and maybe what matters most is the listening, and the open question: Who’s there?

Who’s there?

Who’s there? Who’s there?

Who’s there?

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.