Dancing While the World Burns:

An Interview with McKenzie Wark

In this interview, Callum McLean explores McKenzie Wark's book Raving and, alongside the writer and media scholar, reflects on raving as a cultural practice and a way to navigate a world in crisis.

In a dizzying world of unfolding, overlapping crises, it’s hard to know what to think – so why not turn away from thinking altogether? Raving seems to offer that promise.

And it was to raving that McKenzie Wark turned shortly before and during the pandemic, after a rare break from publishing since she began taking hormones in 2018. This Wark is introduced in her book as “a middle-aged, clockable transsexual raver”: a new context for a writer already fairly well known beyond her research circle (mostly in media, critical and cultural theory). Raving has since brought Wark to an even wider audience, and the experience of raving itself has also brought Wark to new places in her own thinking. But does raving as a practice not rule out thinking altogether? And what are we to think at all about raving?

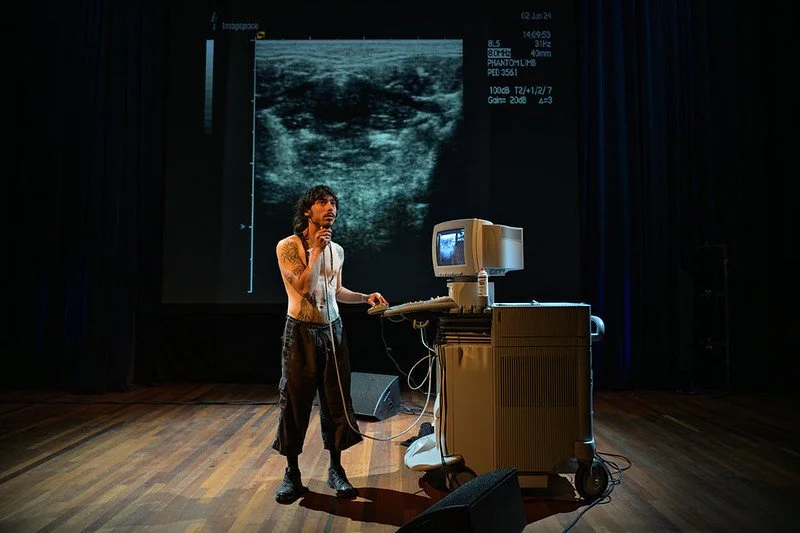

To answer these questions, I spoke with Wark a few weeks after her reading and Q&A as part of the context programme of FIBER Festival 2024 – about raving’s power beyond politics, how raving continues to thrive, and how it might help us all to survive.

But what is raving, actually? For Wark, raving is an embodied practice, and also a cultural phenomenon expressed between bodies. More specifically, it’s a phenomenon experienced in a particular context: by Wark, within queer raves in and around Brooklyn around and during the pandemic. This raving – and perhaps raving in general – reflects, and partly resists, dynamics in the world beyond it. But it also tells us something about that world.

Wark, however, might put it differently: “It's a book for ravers. It's a love letter to the [raving] world and to analogues of this world and other parts of the world.” As so often in the book itself, in our conversation she resists disentangling these perspectives when considering her aims: “How do you centre the history of Black and queer people in the production of this overlapping constellation of electronic dance music, the space of the night club and then rave as a specific set of practices and the history within that?”

McKenzie Wark, Raving, out on Duke University Press.

While Raving confidently takes up this challenge, it’s not a book that offers easy answers to this kind of question. “Raving is kind of a sneaky book,” Wark confirms. “It sneaks in a kind of worldview that engages with certain philosophies into a book about a very specific experience.”

Throughout Raving, anecdote and observation of Wark’s raving experiences often work in this way, to elucidate broader social and political dynamics: to show how ravers are situated in, created by, and reacting against (or at least ‘dissociating’ from) the world outside the rave.

This is also often flipped, when raving and techno themselves come to symbolise and challenge our understanding of time, history, and politics. This is most evocative when Wark wields terms within DJ and club culture as metaphors – synaesthetic descriptors for reality, which seems warped as a result: "Cross-fade to now. That memory track beatmatched to this in the rave continuum" (p. 16); "Sometimes when I'm raving, the theory sequencer kicks off on its own. Concepts dance into the sound" (p. 30).

But it’s also by and large a book for these specific ravers, about these specific raves. Wark explains: “I want to be able to have a space of reflection for the [raving] world itself. Not everyone in the rave world wants that, but for me and others, we'll stagger out of the party and be like, ‘What the fuck just happened? We need to talk about that.’”

This drive is perhaps what makes the book so readable. It’s impossible to resist its thick description of dance floors: from the jumble of jostling crowds and sexual encounters to the phantasmagoria of dancing bodies lost in “ravespace”, transcending to “k-time”. As these seemingly heady concepts imply, those vividly lived moments are often carried to conceptual conclusions, embodying Wark’s more scholarly thoughts about the world at large – but they are also there in service of capturing and doing justice to the uniqueness of those raves. In this way, the book can also be read quite straightforwardly as a rave report, a celebration of raving. “There's moments at the rave that are just so astonishing that you have to rise to the challenge of it,” summarises Wark. “There's a whole history to nightlife and techno and whatever, but the flavour of this one in particular is this very rich, specific thing.”

The alien clamor of computation patterns a chronic 140-bpm situation. The dense, hot, wet, beat-stricken air, teaming and teeming with noise, sticks like meniscus, passing perturbations through skin as if skin’s not there. It’s all movement, limbs and heads and tech and light and air bobbing in an analogue wave streaming off the glint of digital particles. Getting free.

Raving, p. 18

The appeal of this style and of these detailed rave reports is self-evident and broad. But it could be broader, clarifies Wark: “I don't want this to be a book for tourists”. Throughout, she obfuscates names of raves and ravers, to protect the culture and individuals within it – from social and workplace judgements of raving’s sexual and chemical liberties, but also from scrutiny around stories of “crisis” and addiction. “There's just so much trauma in this little world that sometimes it comes out in behaviour that you wouldn't accept in the straight world. But here it's like, ‘Yeah, honey, we're all like that.’ So it's about having that compassion for that.”

Compassion and respect, for Wark, are more than just questions of writerly ethics. They define good praxis at the rave, and help distinguish her and her role in the rave from its core characters. “It's all about respect and honouring who really needs these spaces”, Wark emphasises. “For me, at the centre of it are the ‘dolls’: it's certain kinds of trans women, often trans women of colour, who when they show up at the party, it's been blessed. That's the place to be: they feel at home here, at least for now. So this is the place, and let's let them have that centre of the dance floor”.

Despite herself being a core part of this culture, Wark repeatedly insists – in the book, and our conversation – that she is not raving’s main protagonist. Among the colourful characters of Wark’s raves, she defines certain subcultural archetypes defined in contrast to the doll: “coworkers”, who are guests in the rave (“I'm also a ‘coworker’, in this context, just meaning someone with a day job”, she clarifies), and “punishers”, usually cis male dancers taking up too much space (“someone who is going to make it hard to get your rave on” [p3]). While Wark’s subjective experience of the rave drives the book and its conceptual directions, these reflections are not presented as its end goal. Introspection is very much not the point of raving, or of the book Raving. Wark explains: “I think it's more just that sensibility of making oneself a minor character in this, or making one's type of person a minor character in the history… this has all been about somebody else from the jump. It’s to honour that.”

In fact, Wark emphasises, losing sight of this is what threatens raving, or kills its buzz. The self-conscious fetishising of authentic rave – and its dolls – is what draws the punishers. “Wherever it looks like there's people actually having a good time, then a style has to be extracted from that to be turned into a commodity to sell,” explains Wark. “But it won't be the good time: it'll just be a sign in place of the good time. That can't work! You have to work it, you know. Like the saying goes: ‘work it!’ [The rave] is not something to consume, it's a thing you make.”

Yet this cycle of commodification is nothing new, and raving – in queer Brooklyn and elsewhere – can survive it. This co-opting or, to use a term from the Situationists (one of the core topics of Wark’s previous research), “recuperation” is a feature that seems fundamental to cultural (re)production in late capitalism. “That's the history of Black culture: it’s been recuperated for 100 years. The whole history of recorded music has been involved in this recuperation: this is just the latest wrinkle on it…

“For now, [queer Brooklyn raving] is ongoing! The rents are fucking killing us. That's what'll drive us out of the city, eventually: landlordism... Otherwise, as long as we can make rent, we'll make a world: we'll make a world and it’ll be fabulous.”

***

In this cat and mouse game, rave is pitted against its enemies: gentrification, landlordism, commodification. So it’s tempting to see raving as an antidote to capitalism itself. Since its inception, rave has exuded this kind of mythology: that on its dancefloors are sown the seeds of change, that its sounds carry emancipatory possibilities. “We did that in the ‘90s; I'm just so over it!”, Wark scoffs. “Rave is not utopia. It's not transcendent. It's not resistance. It's just not! On the other hand, it's not [only] escapism either. It's a situation.”

Does that mean rave is not political? On this matter, Wark is passionate and well prepared, so it’s worth quoting her at length: “People always want a politics that’s actually somebody else's: it's from some other place… it's this middle-class straight person's idea of where Politics is, with a capital ‘P’: the political. But politics is every single move you make on the dance floor. At a good party, everybody's there: every kind of body is there – people with very, very different kinds of neurodivergence are there sharing space, and disability and mental illness… On top of all of the genders. It will be a multiracial space.

“We're figuring this out with every single move… We haven't solved racism or whatever – that’s not what this is – but we’re just figuring out how to cohabit this space without having that meta-level commentary about this all the time. We're just together – and working on producing a non-individuated body, working on non-singular being. A good dance floor does that. It's kind of astonishing when it comes off.

“We're all supposed to have these fucking obligations for other people's politics, and no one feels obligated to us. It’s like, Where are you fuckers for the dolls? For the trans women in this town? You don’t show up for us. So fuck you: we're supposed to show up for your thing now?”

“I’m putting it a bit harshly”, Wark admits, but it’s because we seem to have touched on the crux of the matter. For those who don’t “need” the rave, these questions are academic. For those who do, its meaningfulness is intuitive, visceral – and the stakes are infinitely higher. “People who want to do other kinds of politics, what's their responsibility to making it possible for us to do this thing – and without which some of us wouldn't still be alive? I really believe that the dance floor is keeping some of my friends alive and sometimes myself, frankly. So yeah, who's committed to that?”

To exist inside those beats is like hacking into a new brain, one that doesn't hate my body, that can run on the DJ's track and not the track of my anxiety, that allows my body to be a fucking body.

Raving, p. 80

Raving might not be political in a narrow sense, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t significant, or that it doesn’t have something to say about, or to teach, the reality beyond it. Wark articulates: “There are different functions in the world, and I truly believe that there is a power in politics, but there is also a power in culture, there is a power in the social, there is a power in aesthetics.”

And this is where raving’s connections to a wider world materialise. Raving won’t start a revolution, but it does reflect seismic changes on a global scale. “I feel like one of the things that's going on is that [the rave] is a place where people take the emotional outpour of what's really a world historical situation”, Wark clarifies. “That not the world, but a world is ending – and we know it. We all know it. So what's the art form that articulates that? Well, one of them is definitely this.”

The book ends on this note, which seems both apocalyptic and oddly hopeful at the same time. Are we just raving to distract ourselves while the world burns? Perhaps, but in this moment of shared catastrophe, raving presents a practice that turns to the collective nature of our predicament – and that centres those who are usually sidelined from our idea of who gets to matter in this struggle. The rave offers answers here: “Here is a place where an artform is working through that intense emotional experience. And it's going to centre people for whom the world never existed to end in the first place, you know? Trans women of colour never had a fucking world in this country.”

This turn to raving’s main protagonists is in this way a double one. It affirms the particularity of their traumas and also their relevance for us all – not to fetishise them, but to champion them and their modes of survival. In particular, Wark articulates the cultural connection of raving – as a personal, embodied practice – to our world historical moment through the concept of dissociation. “I think [dissociation] is a different sort of aesthetic category based on an experience that gets pathologised but is actually a sort of social artefact.” To be clear, Wark cautions, “dissociation is not a good thing. To be exiled from your own body is really not fun. On the other hand, if it is going to happen, how is it a thing that you can train to give you experiences that enable you to re-associate to something, to re-associate to the collective body of the dance floor, for example. It’s not going to work for everybody, but I think for some trans people and otherwise traumatised people, there's things that we make dissociation do for us. And [the question] is, maybe, What if dissociation was a sort of aesthetic key to the era?”

As Wark explains, the concept of dissociation responds to our era of crises in a similar way than “alienation” once worked, in the ‘60s and ‘70s – to link our individual experience to global processes. Then, the concept argued, we lost our collective power. This time, it’s about coming back together.

There is merit in sharing the pessimism. Everyone is experiencing it. Helps us all feel our way through it. A commiseration. An articulation. It makes it okay not to pretend that some big hope is going to save us. It’s about how a person saves herself, inside of this darkness, at the end of the world, by finding some way to exist within it.

Raving, p. 85

“Raving is not just a book about the rave”, Wark insists. Of course, on one level it is about the rave as a rave. But it also shows how raving responds to a collapsing world, and how it might offer hope for those of us collapsing along with it. “It’s a book about aesthetics: the aesthetics of dissociation and historical time”, Wark summarises. “[It asks,] How do we manage being in the world at this time, when a world is ending?”

Faced with questions of this scale, Wark insists, there are no easy answers or magic bullets. But there is always raving.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.