Bodies of Difference: Ramon Amaro on Machine Learning, Race, and Reimagining Technology

In this article, Eleni Maragkou explores Dr. Ramon Amaro’s work on machine learning and its intersection with race, technology, and power. Amaro’s book, “The Black Technical Object: On Machine Learning and the Aspiration of Black Being”, examines the complex relationship between race and machine learning and alternative approaches to contemporary algorithmic practices, challenging us to envision more inclusive and generative futures beyond the current limitations of machine learning.

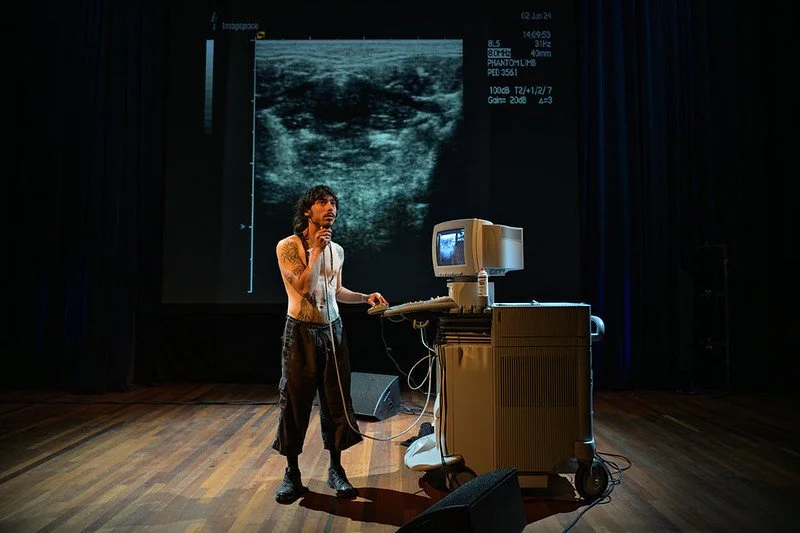

Ryo Ikeshiro, Ethnic Diversity in Sites of Cultural Activity, 2014-ongoing, Image of performance at Chisenhale Art Place, London, 2015. Ryo Ikeshiro.

“I would feel better if they went to Mars because then it would at least make sense,” says Dr. Ramon Amaro toward the end of his conversation with Abdo Hassan during the second day of FIBER Festival’s context programme. “But all this has actually done is correct my typing on Outlook?” Laughter echoes in the Grote Zaal of de Brakke Grond.

Here, Amaro refers to the trillion-dollar AI industry that, in his view, suffers from an “imagination problem.” His most recent book, The Black Technical Object: On Machine Learning and the Aspiration of Black Being, published by Sternberg Press, is a deep contemplation of machine learning, mathematics, and the incursion of racial hierarchy. In the book, Amaro explores the history of statistical analysis and scientific racism in machine learning, framing it as a way to disrupt the racial ordering of the world.

Each chapter is written for different audiences—engineers, philosophers, and laypeople—with the aim of sparking a reconsideration of one's position within this technological ecology, regardless of background. As a writer with a deep interest in algorithmic cultures, datafication, and the proliferation of AI imaginaries, but admittedly a deficit in knowledge of programming and mathematics, I sought to understand more — and had to look to the source. Over the summer, I spoke with Amaro, who offered further context on his perspective regarding machine learning, computation, and the role of technology in society.

“I’m advocating for a type of non-linear computation, [...] a non-linear process which incorporates all the messiness that we sort of have,” Amaro states. He suggests that abstraction, quantum tools, and non-linear computing—concepts that go beyond conventional linear frameworks—can help us reimagine life and identity beyond the limitations of computation. “But to achieve that, I felt I needed to perform and engage with this concept myself. So the book is actually written in a circle, but the complication of a written text is that it appears linear.”

Within this circular structure, Amaro navigates various nodes of knowledge from multiple perspectives. One chapter delves into racialised logics, highlighting the ongoing disparities faced by Black and Brown people globally. Another is directed at engineers, encouraging them to reflect on their daily practices from a philosophical standpoint. A further chapter offers an in-depth exegesis on machine learning foundations. Recognising that not everyone is versed in mathematics, Amaro approaches the subject in a non-mathematical way, focusing on its implications rather than the technicalities.There are also speculative chapters that are purely philosophical, exploring various critical and philosophical concepts to help the next generation of critical theorists engage with emerging technologies.

Amaro began his career as a mechanical engineer, focussing on design quality at a major automotive company in the US. During this period, he became acutely aware of the human element in technical problems: "It was very difficult to solve these problems, these technical problems, because the human element went sort of unnoticed, and there weren't really languages that, you know, within the facility to even think about the human sort of intervention."

Seeking to understand this tension better, Amaro transitioned to policy work in New York with the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. As a program manager for the alternative fuels group, he worked with experts across government, military, and academia, deepening his understanding of how human elements influence technological policy and discourse. This experience led Amaro back to academia, where he pursued a master's in sociological research methods and later a PhD in the philosophy of technology. His academic journey allowed him to explore racial dynamics, social justice, and the impact of advanced technological systems such as machine learning and AI. “It's really where I began to, during the master's, where I began to really think more deeply about racial dynamics, social justice, but also thinking about sort of bodies of difference.”

Ramon Amaro, The Black Technical Object, out on Sternberg Press.

Discriminatory Data and Datafied Discrimination

In the last decade, many critical works have been published focusing on data discrimination and the ways in which data is intimately tied to power and knowledge. Within this realm, a paradox arises: that of the invisibility and hypervisibility of racialised subjects. Black people, though not represented in data sets, are hypervisible in visual culture and discriminated against by systems that are not necessarily explicitly trained to be racist, but, rather, are dominated by whiteness as neutral:

race-free =/= racism-freeWhen coherence and detectability are necessary components of human-techno relations, and illegibility poses a threat, it becomes tempting to turn to the optimisation of algorithms to widen the breadth of what they consider human, rather than to explode those categories all together.

In his book, Amaro addresses direct confrontation with the Eurocentric constructions of ‘humanness’, articulated as the trope of the white cis, heterosexual cis male as the ‘apex of species’. Through processes of the Enlightenment, eugenics, industrialism, and mainly humanism, we began to develop these hierarchies of different types of beings, but also of different types of humans.

These hierarchies articulate themselves into certain categories, whether these be racialised, geographic, gendered, or species-based, for example. Drawing from a critique of anthropocentrism and technological solutionism, Amaro considers technology beyond and in spite of what it can do for us. “That's part of the problem.” He argues that humans are always looking towards technology to teach us something. “We've reduced technology to being functional, for the purposes of gain. Along with that, we began to reduce all social behaviour to being functional, available for gain. Included within that is the racialised body. So there's your colonialism, your chattel slavery. These people are no longer humans, they're just labour to enact another type of process.” The racialised body is then recognised only inasmuch as it can be made recognisable via empirical (and imperial) forms of knowledge.

Even within the duress of that interruption to life, whether it be race or technology or so on and so forth, there's a generation of positive affirmative life that continues to flow throughout the world. “Palestinians are still generating life,” says Amaro. Livability, whether it's a smile, whether it's the sharing of water, whether it's the building, helping each other build a tent, whether it's helping each other get flour or move, it's the generation of life that lives despite the immediate danger and the duress that's there.”

There lies a tension between the reduction and the generation of life within algorithmic processes. When we focus on how algorithms reduce complex human experiences, we overlook their potential to generate new possibilities, particularly for reimagining Blackness beyond its historical associations with suffering. How can these processes open up new forms of generative and affirmative life?

Amaro proposes a regenerative co-participatory relationship with technology: “Just as we need to gain a different relationship with water resources, with plants, with biodiversity, what I'm saying is that, however it emerged, whether we like it or not, advanced technologies are here, and we created these advanced technologies.” But that first requires us to change our perceptions of these tools. “What I'm trying to show [in my book] is that we keep missing the moments of human reflection, because we're waiting for something to tell us what we already know. How is it possible on this planet, in this year, in 2024, given our global history of genocide, of colonialism, of chattel slavery, of local violences, of all police violences, why do we need an algorithm to tell us we're racist? And why do we need an algorithm to solve it?

Technologies are reified as both the problem and the solution for that which we can't face. “So really what we're doing, and what I'm arguing in the book, is we keep outsourcing our own problems onto the same thing we're blaming for showing us the problem that we have. It's an abusive cycle.”

Who are the beings within the human species, and even beyond it, who are seen as outside of the apex of what a prototypical sense of a being would be? To counter this, Amaro uses the word Black with a capital B to encompass this global body, this being of difference. “The body is very limited to the idea of who we are as human beings and how we participate in the world.”

Difference is, argues Amaro, a direct confrontation to the construction of the idea of what a human is. This idea, which emerged through Western Europe, has been articulated in the form of the trope of the white heterosexual cis male as the apex of the species. Through these processes of the Enlightenment, eugenics, industrialism, and mainly humanism, we began to develop these hierarchies of different types of humans, with one type positioned as more valuable than others. For Amaro, the body of difference is the being within the human species, and even beyond the human species — that which is seen as existing beyond the prototypical sense of what a human being would be. That difference articulates itself into certain categories, whether these are racialised, geographic, sexual, or gendered.

These logics of categorisation and classification on the basis of perceived economic or political value are enduring in their ability to stall the building of self-knowledge in the present while also regulating via surveillance, the existence of certain bodies, extending control beyond the corporeal body. In algorithmic culture, the Black object, historically pre-conditioned by racial perceptions, becomes a site of both limitation and potential. Machine learning and AI are shaped by imperial expansion and operate within colonial frameworks and Aristotelian modes of truth, reducing the lived possibilities of Black life. Is a genuinely progressive, participatory AI needed or even possible?

If oppressive structures are baked into AI technologies through data, is it enough to just change the data? By focusing on affirmative potential and the possibility of a “right of refusal” to representation, Amaro challenges these systems’ narrow focus on inclusion. Blackness can generate new forms of being, even under historical and structural duress.

Image generated by the author using OpenArt. Prompt: Detailed, HD realistic colourful representation of a machine learning algorithm in the style of a Baroque painting.

Platform Realism, AI Aesthetics, and the Metaphors We Live By

What intelligence do we actually refer to when we speak of artificial intelligence? Can a machine learn? Metaphors are heuristic tools that allow us to grasp concepts through the use of language that is familiar to us. “The concept of the metaphor is quite powerful, because it cognitively taps into different portions of our being and our neural systems, and interacts with memory and visual perception. The human species has always worked through metaphor, through the complication of visuality and ephemeral concepts.”

Historically, especially in communal and Indigenous cultures, transgenerational knowledge has been transferred through fables, parables, and poetry. These conceptual ideas have allowed individuals to see themselves within the narrative. For example, consider parables. Amaro recounts one where a man is crossing a lake with a scorpion in his pocket. This imagery helps us connect with the story on a deeper level; “Maybe that scorpion is another human being or it’s a process or it’s a political structure.”

These types of structures are also present within AI and machine learning, and they ostensibly serve the same type of function, by breaking our perceptual lens and allowing us to feel, experience, be in the moment and then therefore gain a sense of agency in which to participate in that moment itself. “And this is why I'm so against the debate in AI about what's real and what's not real,” says Amaro. “Because the scorpion in your pocket doesn't have to be real for you to learn the lesson, because the real transformation will come with your connection to a larger body of wisdom and knowledge itself.”

Sycophants often tout the supposed ability of AI to “realistically” reproduce reality[1]—as if such a process can ever be carried out. Yet these claims obscure how the emergence of such aesthetics ascertains the status quo; the process by which a written prompt is transmuted into an image is by no means neutral, but rather subscribes to algorithmic logics, which in turn attempt to, in the words of Flavia Dzodan, “render the complex and particular into legible, aspirational forms.”[3]

I stirred the subject of my conversation with Amaro toward the viral proliferation of an AI-generated image of what is ostensibly supposed to be a refugee camp, though what is absent from it is more important than what is present. Bearing the text “ALL EYES ON RAFAH”, the image is bereft of any human element. Shared millions of times, it became memefied and subsequently drew critique for its sedimentation of a sanitised representation of genocide and dispossession. Admittedly, Amaro’s answer takes me by surprise.

“When you make a caricature of a political statement in a cartoon, that's not a real depiction either. But it's distributing a message,” he says. “We don't need AI to tell us that there are millions of people who are displaced and in danger. I don't care if it represents reality, because I know reality; I don't need to see it. Before AI, we had the propaganda poster, the placard with a funny message or something else like that might not even depict reality,” he continues, “but we don't blame the cardboard for saying, hey, you're not depicting the world as it really is. And it's not representative of the world.” For Amaro, the problem boils down to subsuming this into an issue of what's the truth, what's a lie. “While we're debating on whether this image is real or not, there are babies dying. Who cares? Who cares if this image is real or not?”

This seems to be a leitmotif in discourse around “new” technologies: “We ignore the real issue, and then we subsume the most superficial of that issue, and then that's what we debate. It's a moment of safety because we can't face the complication of what's going on. And what Gaza is currently representing now is a particular Western crisis.

“Humanism has prided and valued itself on human rights, on the capability of expressing rights, on what it thought was life itself. Yet and now in many cases it's supporting the destruction of life once again. So instead of us addressing that, we want to look at an image and do an analysis of, you know, was that tint generated by AI or was it a real tint? Is it a distraction?”

History has already shown that what we see, we're not ready to see reality. We've seen it historically. How many more times do we have to see it? We cross homeless people and rough sleepers all the time, every day.”

“The problem is that we're demanding people have solutions when we ourselves don't even have a solution,” says Amaro. “Do you know how many times I get asked, well, what's the solution to race? If I had a solution to race, I'd be on a yacht right now.” The idea that a single human being, let alone a tech giant, ought to possess that singular panacea is absurd. “I'm not giving that solution to Mark Zuckerberg, right? I don't expect him to have it, because no single human being should possess that much power.”

Towards a More-Than-Human View of Technology

Cultural imaginaries around AI oscillate between production and destruction. Writer Jason Parham writes that “[the] awe of what AI will achieve is undeniable. But so is the fear.” When not concerned with how it will help make our lives easier, AI is shrouded in a public epistemology of fear: the technology can be weaponised against humanity, peace or democracy, it reproduces harmful norms. Writer Jason Parham writes that “[g]enerative AI pulls from—learns from—the ugliness of human error.” If it isn’t discussed as a harbinger of catastrophe, AI is understood as a solutionist panacea, a ‘surrogate’ technology, a tool on which we (ought to) rely to show us reality, do the chores, solve our problems. Even leftist outlooks on automation hold this view.

It’s of course tempting to look towards technology for solutions, but Amaro is not concerned with what it can do for us. “We're always taking this anthropocentric position, assuming we’re this apex of species on a biodiverse planet, by saying that it’s Other’s job to teach us something. I'm trying to reposition our relationship with technology away from that idea.”

This is of course easier said than done. Powerful, heavy, financially viable conglomerates have decided what these technologies will do for humanity. How do we tip the scales back towards alternative forms of sociality, in tandem with these technologies? “What we have to do, and here's the kicker, here's the problem, is we have to get rid of the aim, we have to get rid of the idea that these technologies are useful only for commercial aims,” says Amaro.

In spite of all the currency that has been spent, and all the talent and brain energy, the only thing that we can really produce is a sophisticated language model that can write an email for us. “Because that's sellable,” Amaro says. “Whereas you see alternative practices, small pockets of communities, First Peoples, Inuit Peoples, Indigenous communities, Black, Brown folks, trans folks, artists and makers who are trying to break that system and come up with alternative languages in which these technologies can express something different, imagine a world where the principal concern of technology isn't fattening a bank account.”

Amaro likens this with the situation of someone squatting in your house, leaving you to spend the rest of your life standing outside of your own home. “This is why I want people to not do machine learning,” he says. “I want people to learn what it is, because I want people to go into the house and see who's real and who's a fiction. To see that actually the individuals we see as all-powerful are all-powerful for certain reasons, and we need to detach ourselves from the idea that those systems are impossible to disrupt.”

Ultimately, in this crisis of imagination, we must, as author Lola Olufemi suggests[3], navigate the space between what is and what could be. We need to cultivate the ability to imagine otherwise—to envision the possibility of disrupting the systems we take for granted.

Notes

[1] This quasi-photorealistic output of generative text-to-image models like Midjourney has been called ‘platform realism’ by Roland Meyer, see this thread on the platform formerly known as Twitter: https://x.com/bildoperationen/status/1693505465542414347

[2] Flavia Dzodan, Amorino Latente / Latent Cupid, lecture delivered at the Sandberg Institute, 26 November 2024.

[2] Lola Olufemi, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise, Hajar Press.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.