The Sound of Nature

Inspired by Els Viaene’s “Vibrant Matter”, a minimalist sound sculpture amplifying nature’s quiet transformations, Kat Milligan reflects on how sound, art, and technology can deepen our connection to the environment and our place within it.

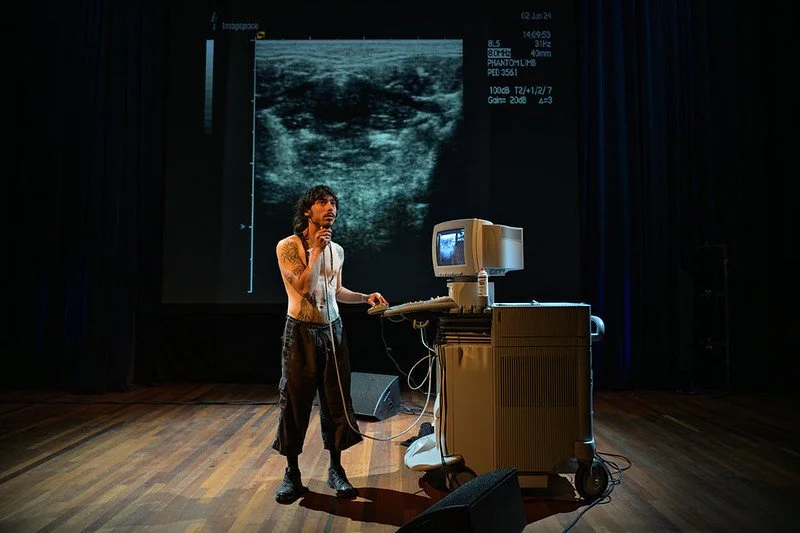

“Vibrant Matter” by Els Vienae, shown during the Neighbouring Frequencies exhibition.

Photo credit: Pieter Kers.

FIBER Festival is known for opening interesting dialogues around a specific theme, inviting curiosity through a multi-sensory program that explores creative developments in art, sound, technology, ecology, and narratives important for society. This year, the theme was Outer/Body, which explored our connection to the environment, extraterrestrial life, AI, and how external stimuli, particularly sound, can affect our emotions, be that as a calming force or provoking nervousness. Each performance, exhibit, talk, or workshop pushed the boundaries of how music, art, and technology interact with the human experience. One piece in particular caught my attention; Vibrant Matter, a minimalist audio-based sculpture by Flemish sound artist Els Viaene, which fit into the Outer/Body theme by dialoguing the natural world.

Viaene’s work focuses on the interaction between human perception and environmental sound. As a field recordist, she is intrigued by how we see and hear the world, and how these senses can interfere or complement one another. Her practice magnifies the hidden, often overlooked sounds of nature and turns them into an immersive experience. This interaction with landscapes through sound reflects her deep interest in revealing the subtleties of our environment, challenging us to listen and reflect on the relationship between sound, nature, art and our imaginations.

FIBER Festival showcased Viaene’s piece “Vibrant Matter” (2016), which is a kinetic sculpture where a sheet of paper is manipulated by magnets, creating a soft, crackling sound amplified to mimic the slow, hidden audible shifts of the landscape. Inspired by her fieldwork in Iceland, the piece evokes the slow melting of ice and geological movements beneath the Earth’s surface. What fascinated me most was how the entire composition of this work asked us to focus on the small, often unnoticed transformations in the landscape, those quiet processes we rarely pay attention to.

The beauty here is not in the crashing waves, the dramatic rumble of thunder, or the melodic song of a bird, the usual suspects when we think of “natural sounds.” It is in the quiet, persistent erosion of time and the landscape’s slow metamorphosis, something we are generally used to seeing documentaries as a time lapse, but not properly listening to.

Plantasia (1976), Ambient 4: On Land (1982), Green (1986)

By connecting nature, sound and imagination, the piece really got me thinking about the links between nature and sound, or more specifically music, on a larger scale. Immediately, Brian Eno, and his ambient music, sprang to mind. In his album Ambient 4: On Land (1982), he blends field recordings with synthesised sounds to create immersive soundscapes reflecting specific environments. Rather than trying to replicate nature exactly, he uses sound to conjure impressions of marshes, forests, and coastlines. Other extremely immersive and serene examples of this are from Japanese artists Hiroshi Yoshimura and Takashi Kokubo. Albums like Yoshimura’s Green (1986) and Kokubo’s Get At The Wave (1987) incorporate the sounds of birds, flowing water, and wind, creating soundscapes that take the listener on a musical journey to an authentically imagined natural world.

An album that is impossible not to mention when considering nature and music is Plantasia (1976) by Mort Garson, which was composed specifically for plants. This incredibly imaginative and quirky example of nature-inspired music twists the tale of inspiration, by creating an electronic sound for the natural world, narrating an interaction with nature on another level. While this album does go beyond integrating field recordings into a track to denote similarities to landscapes, it does again merge sound and ecology in a symbiotic way, blurring the lines between the organic and synthetic.

Similarly, one of my all time favourites, Bartosz Kruczyński’s Baltic Beat series explicitly connects his music to a range of natural environments, with field recordings made in places such as Warsaw, Chełm, Hordzieżka village, Ostia, and Parco degli Acquedotti in Rome. The first album, Baltic Beat (2016), and its follow-up, Baltic Beat II (2018), feature delicate, atmospheric tracks that evoke elements like coastal winds, rustling reeds, and quiet forests. By incorporating these field recordings alongside gentle instrumentation, Kruczyński creates soundscapes that transport listeners to the serene, untouched landscapes that inspired him.

Although she does not use field recordings, Mary Lattimore plays the harp beautifully and many of her tracks are dreamlike sonic landscapes, often reflecting the calm, expansiveness of the natural world. She’s another personal favourite of mine and I feel her music conjures images of open air, flowing water, and encourages moments of stillness. Though not directly “nature-based” her work captures the spirit of nature and offers an imaginative reflection on its serenity.

All of the artists mentioned here play with the connection between sound and nature, often using their creativity and imagination to mimic natural sounds and create soundscapes that replicate the calming sensation of being alone in a forest, or standing by the coast with the wind in your hair. This act of reimagining natural sounds is a vital part of why this type of music has proven to be so mentally healing. But why?

In our busy lives, many of us lack access to nature and its restorative qualities every day; ambient music offers us a chance to reconnect. It is actually proven that just 15 minutes in nature can have lasting effects on the body for up to two weeks. Perhaps we simulate that same connection through these soundscapes? They allow us to pause, breathe, and experience the subtlety and wonder of the natural world, even if only in a sonic form. By immersing ourselves in these reimagined environments, we can be reminded of nature’s intrinsic value.

This brings me back to Els Viaene’s Vibrant Matter and Outer/Body. In Vibrant Matter, Viaene celebrates the processes occurring beneath the Earth’s surface, the hidden tensions, and in doing so, she reminds us that sound is not just something we hear but something we feel, something that can connect us more deeply to our environment. By channelling nature into art, we seek to capture its profound impact on our senses and souls, using it as a mirror to express our own “outer/body” experiences.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetry, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.