The Future of Care:

In Conversation with Camille Sapara Barton and Lou Drago

In this essay, Narjollet touches upon the politics of care, technology, and the “future” through an analysis of installations by Roel Heremans and Marco Donnarumma, presented during FIBER Festival 2024, alongside interviews with artists Lou Drago and Camille Sapara Barton.

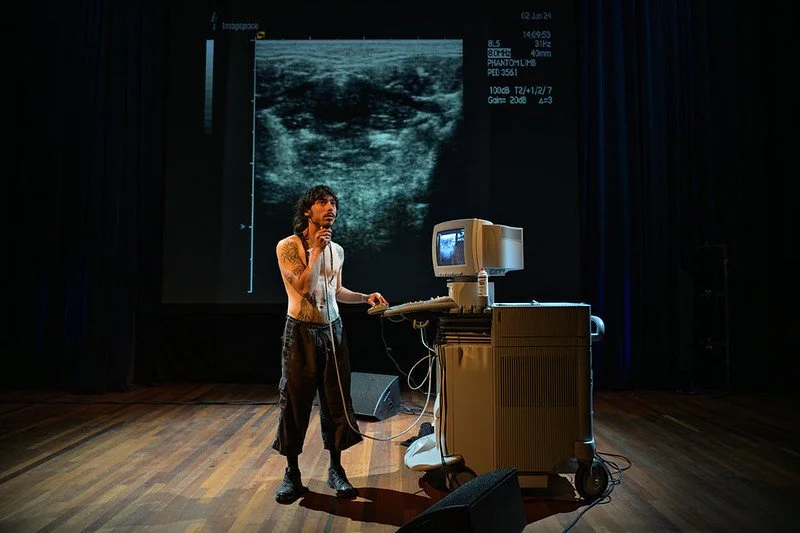

Marco Donnarumma, Niranthea. Photo credit: Pieter Kers.

In a world obsessed with progress and optimisation, it should not come as a surprise that even the technologies created to assist, to help, to care for human beings promote the efficiency of the body as a working machine. This operates to the detriment of an increasingly large portion of the world population as technologies advance further into the body and become exponentially expensive. And as we try to imagine new utopias, it seems that the “future” has been adopted by nation states and their associated productions as an amalgam for the linear, progress-sanctioned exploitation of human and planetary resources. So we are faced with the failures of the word for “future” and the word for “care”, the bankruptcy of their meaning. What practices emerge from this discrepancy of sense? How do artists bypass these constructions when observing and constructing forms of care and healing? This year’s FIBER Festival programme stressed the particularities of this crisis, found at the intersection of technology and care politics.

This essay will first examine the works of Marco Donnarumma and Roel Heremans presented during the exhibition Outer/Body, which relayed some of the many discrepancies of the current Western systems of care. Their installations relayed important research on the politics of prosthetics and neuro-wearables—introducing their audience to the theoretical groundwork of care politics under capitalism. While these artists worked to describe, reveal and document the complexities of western care politics, others introduced their efforts in subverting them.

As technology advances further into human lives and bodies, issues of care and access to care take on exponential importance. In a second part, the essay will turn to Camille Sapara Barton and Lou Drago, who presented their artistic practices during the panel “Careful Encounters: New Forms of Collectivity for Sharing Healing Practices” as part of the Fiber Festival context programme. Through an emphasis on embodied ethics and grief work, they demonstrate the potential of art making to re-shape imaginaries and to actualise alternative conceptions of care.

Roel Heremans, The NeuroRights Arcades. Photo credit: Pieter Kers.

“In the future, neuro-wearables and brain-computer-interfaces (BCIs) will create new and interesting possibilities, obtaining direct information from our brains and influencing our thoughts and feelings. But what happens when companies or governments use these technologies for purposes we do not agree with […]?” Thus reads the description text of The NeuroRight Arcades, an installation by Roel Heremans on the emerging politics of bio-data ownership and physically intrusive technologies[1]. The piece consists of a few arcade machines with which the audience can interact through a joystick, two buttons, and a headset that detects and processes certain brain activity.

The game invites you to imagine different situations in which you might be able to adopt the physical or neurological enhancements of your choice. It asks you to consider to what extent they would improve your performance at work, in social situations, or at a given competitive sport. Then your digital host takes over the daydream and ponders the following: what would happen if you were the only one—at your job, in your friend group, at your sports tournament—without access to these enhancements? Under the shiny side of the coin, the promise of technology that surpasses you to your benefit, the much darker outline of accessibility politics rears its head. Heremans’ focus is directed at issues of bio-data ownership, bodily autonomy and privacy as drafted in the NeuroRight ethical framework. But what transpires from the artwork is the following question: who will have access to the technologies that are underway, that are hailed as the future of humanity?

In the given scenarios, there is one who has access and one who does not. One who can store and process information twice as easily and one who cannot. These enhancements could not only create new problematics of ownership and bodily autonomy but also new stratifications, new tiers of accessibility. If soon parts of the population will be able to access new heights of neurological and physical performances for a price, exponentially large portions of the world population will be left behind as a select few get ahead. Like good science fiction, The NeuroRight Arcades suggests that this future is only an exaggeration, a caricature of the present.

A neighbouring work hosted at the Outer/Body exhibition gracefully describes the complexities of this present. Marco Donnarumma’s Niranthea is a multi-sensory video installation that, among other things, explores the layered relationship of the d/Deaf community to prosthetic technology[2]. It first addresses the misconception that all d/Deaf folk want to use hearing aids. It redirects the issue away from deafness itself as something to be fixed, to the exclusivity and hostility of the hearing world. It is not the limited or lack of hearing that represents an obstruction, a dis-ability, it is the effigy of the able body. This portrait has been nurtured by a historically, persistently narrow agenda, namely the capitalist agenda.

To illustrate this, one of the research participants of Donnaruma’s workshop proposes a reflection on who benefits from the production of prostheses, the artificial substitutes for organic body parts. The participant suggests that accessibility apparatus such as hearing aids are equally bound to the principles of maximum profit as any other consumer product. In other words, it is required to meet cost-effective production and insurance coverage criteria. One can reasonably deduce that the efficiency and quality of accessibility equipment is being constantly negotiated based on the benefit of its producers, not its consumers. Even as d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing people are expected to wear prosthetics, they are likely afforded only a fraction of the technology that is available.

Evidently, there seems to be a difference between a profitable accessibility, one based on cost-efficiency and the expansion of an exploitable workforce, and a non-profitable accessibility, one based on comfort and necessity. The former satisfies a demand only to the extent that it facilitates conformity to the requirements of a body that can be “productive”, in the sense that it can produce capital. It goes without saying that planned obsolescence in the production of accessibility equipment can only work against those who use them. It in part ensures that the task of creating a connection, between the d/Deaf and hearing communities in this case, falls on the shoulders of the former, of those considered “dis-abled”: read here, un-productive, un-exploitable.

If technologies of help directed at and added to the body are created with the intention of making it more efficient, more suitable for its insertion into a workforce, it works to maintain an infinitely reduced notion of what is an “able”, an acceptable body. Niranthea proposes that the d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing community is trapped between two invisible thresholds; expected to use prosthetic appliances which may be limited by design. And all of this is exponentially complicated by the cost of accessibility apparatus and access to insurance of potential users. Tiers of accessibility to care already exist, they permeate our world. How much is lost when care is so unevenly distributed?

Under capitalism time itself, chrononormativity, is imposed on us and our bodies to optimize our productivity as a workforce. Health, which as demonstrated is defined by an “able” body, is also deeply intertwined with notions of youth. Companies advised by insurance providers dictate the timeline of the “healthy” body. In this context, the broader timeline for humanity has been pirated by a strict linearity and a kind of technological determinism. The “future” has been appointed as a singular horizon to give a purpose to the consistent exploitation of human resources. Tapping into the accumulated violence of this exploitation, that for many exists on top of the violence of systemic oppression, is discouraged by the structures we evolve in. As Sapara Barton argues, “Under Capitalism, any feelings or states of consciousness that do not support labor and productivity are taboo.”[3]

Camille Sapara Barton & Lou Dragon during FIBER 2024. Photo credits: Léa Shamaa.

During FIBER 2024, I had the privilege of interviewing Camille Sapara Barton and Lou Drago. Both artists attend to these violences that hide in the body and mind by urging for new and old conceptions of health and healing. Their artistic practices are directed at the creation of communal, shared experiences that respond to the current precarity of care. They gracefully demonstrate the potential of art making to re-shape imaginaries and to actualise alternative theories and conceptions of care in the present.

Camille Sapara Barton is an artist, writer and somatic practitioner based in Amsterdam. They focus on addressing and subverting the Western misconception surrounding grief, and strive to create spaces for embodied ethics. Both efforts intentionally and inevitably, represent alternative and radical forms of care. According to Sapara Barton, grief work is crucial for enacting what they call liveable futures, “futures that are going to support the web of life, support as many beings as possible to thrive and to live in an abundant and nourishing way.”[4] In this context, they address our current aversion to grief as symptomatic of the industrialisation, the mechanisation of the human body. The detachment from grief that is demanded from the body and the individual by the power structures that control both results in the acute isolation of people who find themselves in mourning, consciously or unconsciously.

Borrowing from the Dagara perspective on death, their new book Tending Grief observes this phenomenon with a focus on grief that falls outside of the definition that is given, allowed, of it in the West[5]. While we generally think of grief as the pain that accompanies the loss of an individual, and as something that itself affects discrete persons, Sapara Barton calls to attention forms of collective, trans-generational wounds that generate underrepresented, unaddressed emotional and physical violence. The turmoil caused by these wounds lingers in the mind and body of individuals and collectives in much the same ways as what the West defines as grief, but is rarely addressed as such.

The very nature of our times seem to generate anxieties in both individuals and collectives. We often associate grief with the loss of a person or persons, yet we can also grieve “the death of our dreams, the death of our ecology. Grieving futures, grieving pasts that we’ve never known6.” Lou Drago is an artist and researcher based in Berlin. Their work investigates the connections between the healing potential of sound, queer feminisms, and meditative collective practices. They too identify grief as a plural and complex consequence of precarity maintained by capitalist structures. Like Sapara Barton, they believe that creating space to feel and recognise this grief is essential to creating new networks of care. In turn, these networks of care are necessary for producing social change, the kind that might re-imagine the value of human beings not according to labor or profit. The kind that might emphasise the intrinsic right of all to access vital necessities, which allows the value of personal aspiration and interpersonal connection to emerge from the contraption of precarity.

Identifying and tending to this grief is decidedly a non-profitable form of care in as far as it does not maximize instantaneous physical productivity. And so it must operate outside of established distributions of care — either in private organizations, for a price, or in the remaining non-productive spaces. Sapara Barton and Drago rely on spaces dedicated to art, music, nightlife and their hybrids to enact this care as embodied artistic practice. In 2018, Sapara Barton debuted the SanQtuary at Shambala Festival in the UK, a venue dedicated to providing a safe(r) space for the queer attendees of the festival. The SanQtuary hosted DJ sets and performances as well as workshops and activities that focused on harm reduction, specifically in the context of queer nightlife.

According to Sapara Barton, clubs in particular, as non-productive spaces, can become “a catch-all for many different ways of relating. (...) I think there are many people who consciously or unconsciously are using these spaces to grieve. To grieve and to move through discomfort, because there aren't any other containers really. (...) But if people aren't aware of it, it can create some challenging dynamics.” In order to address the often overwhelming combination of this grieving and the increased availability of substances in these spaces, their projects such as the SanQtuary but also Emergent Bass in Berlin, sought to foster the accessibility of resources for dealing with whatever people bring with them to the dance floor. Emergent Bass is an event series centred on dance and music that simultaneously aims to provide theoretical and material resources to its audience. They address the healing potential of sound and movement as well as the importance of the Afro-diasporic influence on House, Techno, and Bass music, the now-staples of Berlin’s underground club culture. Cultural erasure can be at the root of concealed grieving. Through education, intentional and collective movement Emergent Bass offers an entry point into that grief.

Similarly, Drago uses sound to create spaces in which people can tune into concealed tension in the body. Together with their collaborator marum, they host live sonic seances under the name of infinity rug. In a variety of venues across Europe, from disused power stations to clubs, boats or galleries, they aim to center a collective experience extended over entire nights, with musical offerings punctuated by performances and readings, accompanied by sharing of food, textiles, and scents. Currently they are “exploring different bass frequencies and trying to explore where they are each felt in the body, which is very useful for dispersing, moving or shifting energy blockages — allowing energy to flow around the body differently.”[8] They want to experiment with the uses of techno and ambient tracks, to activate the whole body through dance to be able to receive the very subtle frequencies of ambient and drone music. According to Drago, “within the realms of psycho-somatic ailments, [...] sound can be an extremely powerful tool.”[9]

Drago and marum have also premiered a non-verbal edition of infinity rug, Sound as Touch, in which attendees were invited to explore what emerges when refraining from communicating with the voice. For Drago, alleviating the pressure to speak during times of coming-together can be an alternative but extremely powerful way to relate to one another, to listen to the body of the individual and the body of the collective. Attending to grief through artistic practices rooted in care can be an alternative remedy to the current individualism and ableism of care structures.

Ultimately, these works provide accessibility to resources in order to offer an agency, a literacy of care. Both artists rely on embodied ethics in their practices. According to Sapara Barton, “many practitioners will have ethical codes that they identify with, but there's often a big gap between what's written down and what's practised.”[10] For both Sapara Barton and Drago, the embodiment of their values and research in their respective artistic practice is crucial in regards to meaning making but also an end in itself. Their work exists through and at the service of actualising their hopes for socio-cultural change with regards to care.

Drago’s radio show t r a n s i e n c e on Cashmere Radio offers an antidote for the anxieties and pressing questions created by the turbulence and uncertainty of the current times. Bi-monthly, they invite artists to create a musical landscape to soothe anxieties, address existential questions and imagine alternative realities with the possibilities of change and relief. Mixes curated by the host and guest merge to create a liminal space in order to externalise the unaddressed fears and grieving that “ends up getting stuck in the body.”[11] The medium is perhaps the most important part of the project—the radio dispatch. Anybody with access to an internet connection can benefit from this resource in real time or in retrospect.

In 2022, Sapara Barton launched the GEN Grief Toolkit in collaboration with Global Environments Network. In this Toolkit, they compiled research into non-Western practices of tending grief: why they are necessary, how they can alleviate individual and collective pain, and a set of guidelines on how to practice these rituals, alone or in a group, with a related bibliography[12]. This toolkit is also accessible online for free as an interpersonal and educational tool. Resources of this nature are indispensable but often exploited for profit. Sapara Barton emphasized in a disclaimer to this toolkit as well as during our correspondence that proper citation of this toolkit and their work at large is an invaluable form of care “which is often absent in the art world.” Under the conditions of an extremely individualistic, monolithic art market, non-transactional interactions and collective practices are actively discouraged. In this context, resource sharing is also an act of care. So is engaging in creative processes that reject the supremacy of ownership and the author. Proper citation and crediting practices also fall under this effort: the creation and use of these resources aims to emphasise the shared authorship of social work but also the right to recognition of this work.

Roel Heremans, The NeuroRights Arcades. Photo credit: Pieter Kers.

As technological sovereignty is progressively established, the fallacies of profit-based care systems become jarring and highlight how deeply the capitalist system fails to care for people. By adopting a pseudo-scientific technological determinism, capitalist nation states have defined the future as the fulfilment of this profit. Roel Heremans and Marco Donnarumma demonstrate how the current structures for providing public assistance are not only poorly accessible but rest on inadequate foundations of health. The human body is itself treated as a resource, an exploitable object that need only be fixed when it does not, can not, participate in the labor necessary for profit. In this context, there is little public availability of care that falls outside of this definition of the human and its needs.

This crisis of care rests at the intersection of technology, chronology and profit. Lou Drago and Camille Sapara Barton offer a glimpse into the potential of art to investigate and enact different definitions of care based on social justice and a human ecology. They reject the hypnotism of catastrophe by focusing their efforts on embodied ethics—efforts for the creation of the paradigms they hope for in the present. By actively seeking to provide non-transactional experiences, they both work at eroding the capitalist fabric of the art world. Their practices demonstrate the potential for art to merge content and form into social work, a radical form of providing non-profitable care to human beings.

The future of care seems bleak if it continues to be paved with the same stones that dictate the systems of today. It becomes increasingly clear however that artists are bypassing many of the colonially shaped concepts of the human, its shape, its health, its needs. They take on roles and produce material that pushes at the traditional membrane which envelops the standalone artist. Here may lie the hope for care — in the proliferation of such practices in and beyond contemporary art. Here, in the creation of spaces dedicated to the complexity of the human, as it is, a mess of flesh and feeling and affect. As it is, a being of the present.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.