“Imagine the Moon is a Jungle”:

An Interview with Miha Turšič

Mila Narjollet presents a conversation with Miha Turšič on our cultural imaginary of outer space and the relationship between the hard sciences, control and colonialism.

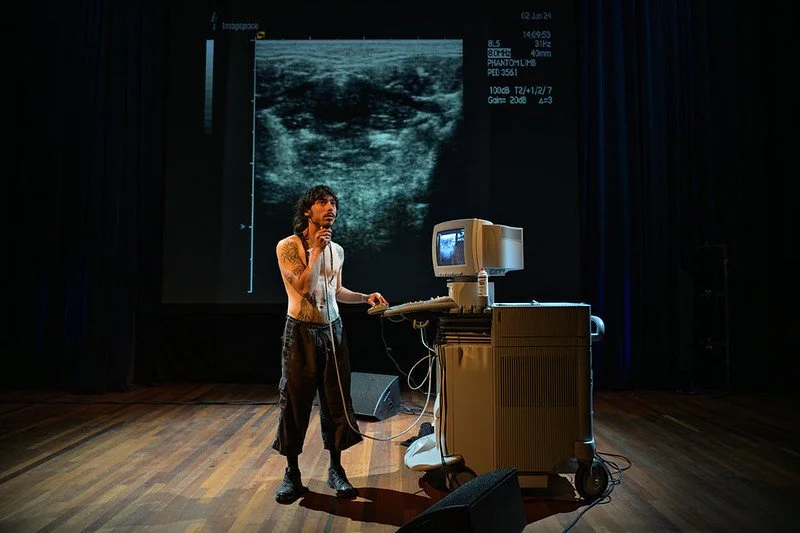

Noordung 1995 2005 2045 @Postgavityart. Image courtesy of Miha Turšič.

Miha Turšič works with what we imagine as completely futuristic media: post-gravitation, space probes, zero gravity or planetary contamination. But these mediums only seem far from us because the public’s access to the hard sciences and their governmental applications has purposefully been restricted. Citizens have no agency over their states’ investigations into outer space because in Turšič’s words, “hard sciences are crucial to technologies of control.” They are wielded in complicated formulations and obscure terms to fulfil the agenda of political and commercial powers. And so a new colonialism operates in the dark, under this esotericism. What is the meaning of declaring a planet barren? What politics lie behind the infamous terra nullis? Miha Turšič’s endeavour is one of distributing knowledge about outer space as a tool to eventually question how our understanding of the night sky has been shaped for us and why. He is pre-occupied with redefining these borders of the outer and the inner - why do we think our body stops at the limbs? Why do we think we are anything other than a part of this sky, of this universe? There is nothing outer about space. It is us. We are it.

Mila Narjollet: Hello, Miha. Thank you very much for meeting with me, I have a lot of questions for you. Your talk raised a lot of questions.

Miha Turšič: It opened questions, yes, that was the intention.

What drew you to the intersection of outer space and art-making was to find organisms and phenomena outside of Earth-bound principles and systems of control. Can you expand on that, on what it means for you to explore these kinds of alien forms of being, of inhabiting space?

In my practice I usually take these very terrestrial concepts, throw them out there, and see what happens. They usually fall apart. When you observe how they fall apart, you find new things that you don't notice here, on Earth. That's why I try to make this comparison, between the internalised and externalised bodies, because whatever we find with the use of space technologies, we view as something other.

We were educated to understand outer space as the outside and Earth as the inside. Though all of the human activity that is out there is part of our established economies and knowledge systems, there are also other realities, non-human activities, that we are not taught to see. So that's why I make the separation between the outer-space, internalised bodies and bodies that actually are emerging from these internalised conceptions. And even bodies escaping them, and those bodies that contaminate economies and systems from the outside. That’s my main interest.

You talk a lot about failure. How important is that for you? Is seeing how things fall apart what you're really interested in?

Failure in the context of unlearning. Having this durational art work—the 50 year project—and then actually learning from practice, instead of imposing my realities. Every artistic practice is quite vulnerable. You are fragile, but if you acknowledge that then it's fine. That's why I have absolutely no frustration in this context. Because I'm here to learn. That is why I am much more positioned in research than in production. And then whatever comes out from these learnings, you make a work out of it.

That sounds so close to the scientific methodology of creating hypotheses and seeing what lands and what doesn't land.

Yes, though they are in an effort of producing truth. I'm not. It's about challenging notions of truth, creating other insights that are more situated.

Your goal is not to find one binary truth.

No, it is much more about acknowledging the plurality of them, and the comparative relations between them, rather than accepting one more than another. I say that they are all equally true though they may exclude each other.

Roscosmoe research, 2018. Image courtesy of Miha Turšič

Do you identify quantum physics and quantum theories within what you're saying? The idea of multiple truths co-existing, is that inspired by quantum superposition?

No, for me quantum physics is too much of a hard science. And why would I have to work with hard science? I can relate, but I don't take it as a point of departure. I'm more interested in other cosmologies and things that are emerging from different cultures, rather than in accepting a dominant physical one. The notion of outer space in physics, astrophysics, particle physics is a relevant body of knowledge, but there are others that are equally relevant. And those are not acknowledged, they're not taken into account in the context of understanding our wider realities. Those are the ones I am interested in.

Then what do you consider outer space? In relation to your practice, is it a medium, is it a resource? Is it a backdrop or something else? A collaborator?

For me outer space is a cultural phenomenon. It’s a way for certain groups of people to construct and try to understand their reality, and to bring in new understandings. More concretely—we do have space stations, we do have satellites, we do have space probes, I'm trying to understand what this means. It’s a cultural study of existing practices. Since this is quite abstract and remote, for me it's important to have a practice, through which to understand what's actually going on. And that's why I see the importance of making art out there. To better understand it. This cannot be an individual effort. It always requires working with other artists, cultural organisations, space organisations.

And that's incredible. There's so many things that I wanted to touch upon, and specifically collaboration—you talk about it a lot. Human but also nonhuman collaboration with the flatworms that you want to send to the moon. Is that really important in your practice?

Always. It's why we work with these platforms and with Symsagittifera roscoffensis flatworms—because we see them as collaborators that help us understand certain things that we don't understand yet. It's very much in the context of ecological ontologies—how things relate to each other. Observing them, their life in relation to the sun, to the moon. And I mean, there are metabolic realities there. So, ingesting the algae, becoming one with the algae, as kind of a photosynthetic animal and then thinking of humans as photosynthetic beings. Studying correlations between the algae, the animal, the sun, the moon, the Earth, and playing with these realities helps you understand phenomena outside of the physical cosmology I mentioned. Things relate to each other in different ways. Being part of a group like the Roscosmoe community or a longterm effort, you can start to see how things function differently.

Is it because you envision some kind of future where we are always in collaboration each other and with other beings?

For me, the future is not really a thing.

That’s so interesting.

I work more on imaginaries, how we construct them. The notion of the future is important for how we imagine. Time is a strong concept, it is imposed on us. How imaginaries are built, how they are constructed, and how they influence us as individuals, as communities, as a society is more important to me. The future is just one of them. Time is just one of them. And in the context of the Anthropocene, I'm more interested in the spatial rather than the temporal, the Anthroposphere: how spatially these phenomena of anthropocentrism are imposed on our environment. And that also relates to outer space; how do we construct these imaginaries? There are these dominant ones like Space X, the colonial, the focus on resources, “let's go there, explore and inhabit new planets.” This is not a question of the future but a question of imaginaries in our heads, and how today they influence our realities, not just in terms of temporal next steps. The notion of future is very political, so my effort is to overcome this power play of those that try to enforce their futures upon us.

And who also make it into such an important thing, who convolute the future with linear progress, and space exploration, which often means colonialism. And this is something I wanted to ask you: is your endeavour also part of making this more clear to other people? Because essentially, this discourse is made very exclusive. I only very recently found out how many space probes there are in outer space. We've essentially colonised a new junkyard, right? Is transparency important to you for your audience to even realise that this is kind of happening in the dark?

There are two efforts in the context of More-Than-Planet. It’s a project that has been running for two years and it is supporting an existing community of artists and thinkers. We have two emerging agendas. One is what we call cultural environmental literacy. That's what you're asking—making things clear, more understandable. Not in the sense of teaching and preaching but as in “let's join our efforts, let's go on a shared journey and learn something together.” It’s about providing resources to those who are curious and want to know more so that they can learn. By themselves.

In this context, we will start building a library of all books on art, culture, and humanities in relation to outer space. So people can learn and have all the knowledge, or as much as possible, available in one place. It’s not one book, it’s a library. This is about literacy. The other effort that we started working on is the question of the public in outer space. Again, the notion of public is claimed by states with their own notion of security. It's claimed by billionaires as civilians. Because a civilian in outer space is some billionaire paying others to go with him. So what are we even talking about? Who is involved?

And that’s about accessibility.

It’s about accessibility, but accessibility exists in the context of inclusive systems. So that’s why we're also interested in parallel independent systems. It's more in the context of diversity. As in, are we allowed to have a cultural space program?

So you’re saying that it's more about diversity because your endeavour is more about questioning the systems that bring up these questions of accessibility.

It's not only about access to existing things, but also having parallel, alternative infrastructures, technologies, knowledge cultures. Who constitutes civil society in the context of outer space? And who does not—primarily who does not. Who are the possible stakeholders? This included researchers investigating indigenous outer space ambitions or practices that exist in entirely different cosmologies. We are interested in open source technologies that allow anyone to build their own ground station or satellite. There are hackers making their own infrastructures, having their satellites out there and challenging existing government systems with a more concern-driven agenda. It’s relevant to question why we're not allowed certain kinds of things. Here you get to the issue of governing outer space, where the notion of public or civil is actually not taken into account. Because it's really about the state, industrial and scientific interests, and the rest are dismissed as so-called nonprofessionals.

And these questions are really not accessible to the public. We're really not used to even thinking about this.

The space community is not open to the public. And that is a symptom. What you just said is a symptom of you as a public, as a citizen. You don't have access. There are no doors, there are no institutions. You can enter through this kind of science popularisation, communication under their narratives, but you have no basic knowledge of having your own agency.

No, it just doesn’t exist. Do you find that this is also partly because space, astrophysics and the hard sciences, are very exclusive and always deal in complex, complicated terms in order to separate populations and knowledge?

I mean, hard science is power. It is related to power. Because hard sciences are crucial to technologies of control. Whoever has this knowledge has access to control. And whoever else wants to work in this field is presented as a risk to their established powers. That was acquired let's say in the last 200 years—a risk and a threat.

More-than-Planet lab at Ars Electronica 2023 @Waag_Futurelab. Image courtesy of Miha Turšič

That's really interesting. I wonder though, because I recently read a little bit about space and the exploration that's going on and where we're at, and I read somewhere that all of the maths and all the physics are there for us to embark on journeys of bringing people out into space and beginning the colonization of the moon, for example. And the reason that it is not happening is because it costs too much. It hinges upon what governments are allowing to happen, and we have no say in this. I find that quite terrifying.

There’s so much to unpack here. So, going to Mars. First, why would you want to go there? There's nothing there. It’s deadly.

Right, and as you said, we would have to constantly have apparatus on us in order to exist as organic bodies there.

Yeah. It’s so deadly, there’s nothing you can do to change it, to make it more habitable. Nothing. So you have to ask yourself, in whose interest is it to get there? And there's only one interest: because there are resources, and they need to build infrastructure to get these resources. Is it in your interest to get resources from Mars or somewhere else? Not really. Because owning the infrastructure and owning these resources gives you power. You don't need this power. You don't need it. So they're looking for investments into their new power structures and access to new resources. And settling Mars, it would be for the so-called labourers. It would be a working camp, not a vacation. We have these parallels in our existing societies, in our history. Colonisers were not tourists. In the context of actual technologies, of the actual economy, space tourism is so minor; it’s just good for their narrative.

So it creates this idea that it’s eventually going to be something that's not just labour-related.

You have to remember that there are 100 workers behind one tourist. So again, we come to the question not of the future but of the imaginaries and what kind of imaginaries are imposed on us, and which ones are not, because they are a threat and a risk. Even being in a critical position toward these mainstream narratives or imaginaries is a threat. And my practice, or my strategy is more about working on alternatives that don't relate to these mainstream narratives. To showcase that other realities are possible. There are other ways of doing things in outer space. Since I don't buy into this internalized approach. This is where artistic infrastructures, artistic institutions, artistic questions are equally relevant. We can do these kinds of things. Things are coming out of our research that are equally relevant.

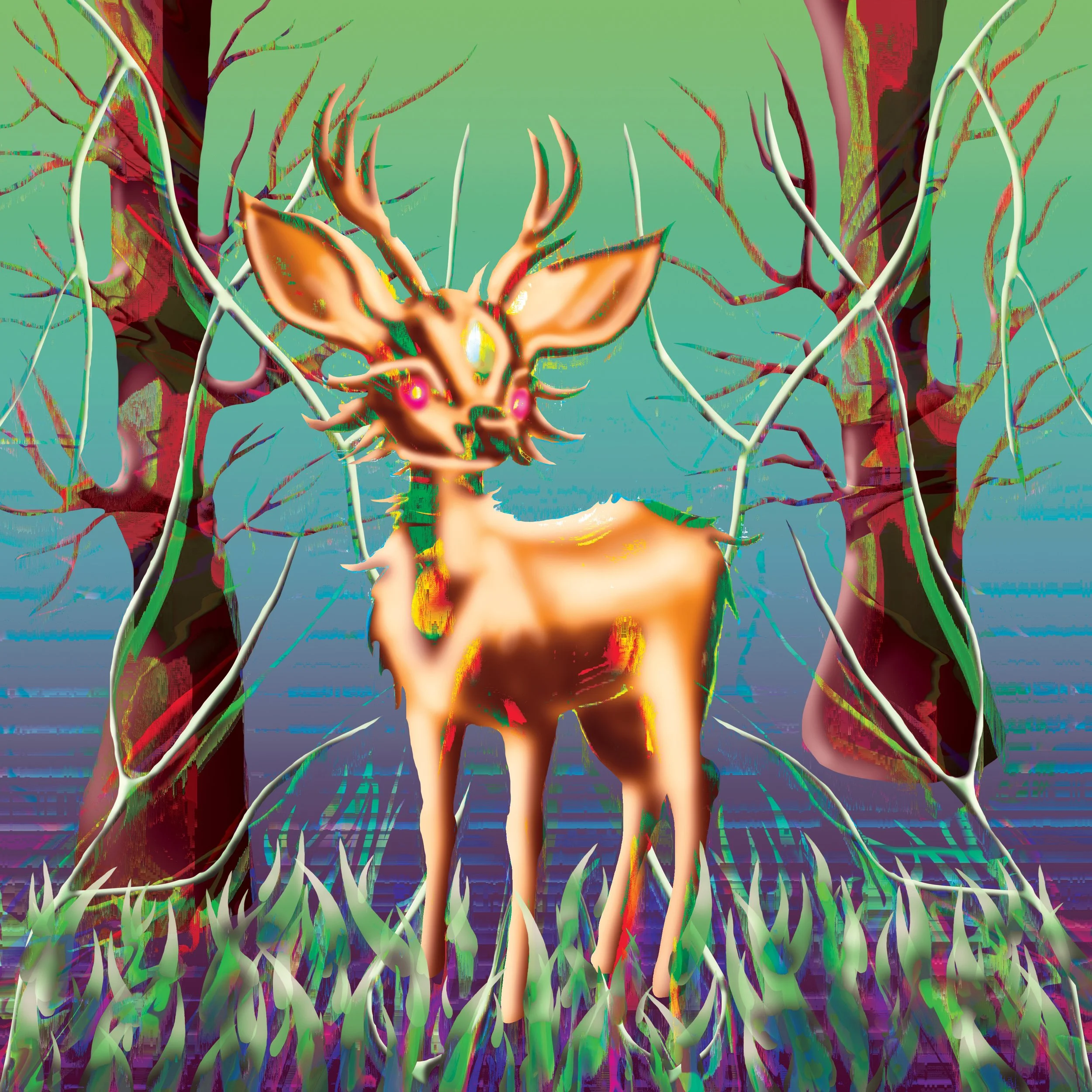

They are imposing the Moon or Mars as a mining destination for all these resources. I would prefer having a jungle all over Mars and the Moon. Something completely inhabitable for us with species that would emerge in those conditions, because they would really prosper into amazing, beautiful planets with such diversity of life. It's less about space technologies and space economies, but space biodiversity. Because we understand biodiversity as a quality these days that has kind of replaced the concept of nature. I want to imagine the Moon as a jungle.

Right, and speaking of imaginaries, the Moon and Mars have been diagnosed as lifeless.

Abiotic, yes.

Abiotic! And that's also what allows us then to imagine them as completely exploitable.

That's the role of planetary protection policies. They prevent anything terrestrial, so life, to grow in outer space so that they can claim territories, not just as terra nullius but also as abiotic. It's not explicit, but it exists in practice. Claiming the Moon as abiotic means you can extract resources there. And that's still an issue on Mars, that's why they are looking for life, or biosignatures on Mars. Eventually when they don't “find anything”, they can claim the territory as a resource. That's my critical understanding.

This is how the imaginary is constructed.

That is how it is constructed in the end, yes, by deciding that we go there, and settle it and that it’s going to be amazing. An amazing mine… To confront these imaginaries I say, “let’s find the jungle, can you imagine a jungle on this planet?” These are over-contaminated planets with such a variety of life that you could never imagine on Earth. And if you don't allow yourself to touch it, only observe it, it's going to be way more beautiful than Earth.

That’s very moving, it’s beautiful.

That's the power of the imaginary that is not positioned in the future, but in the present, because these imaginaries then influence the way we see Earth, the way we act on Earth. It's impossible to imagine Earth as a wild territory. Because at this moment, 90% of the Earth is under human impact. Which means that we impose ourselves, our economies impose on the whole earth. The whole earth is understood through its use. That's the land use concept. The earth is governed through its use to our economies and our states. And there is no space for contamination. Though it still exists. Luckily!

Do you think we sometimes get caught up though in this idea of the Anthropocene? So much so that we give ourselves more credit than is due? We talk about human impact on planetary scales but the Earth has gone through more than one mass extinction. The Earth will exist, based on our current speculations, for as long as the sun exists. Maybe we are just another phase in the life cycle of our planet, do you think that’s an imaginary that needs to be changed?

The concept of our environment needs to change. And all these concepts are political throughout history. The notions of nature and culture have been political all along, it was always about control. Whatever was natural was wild, uncontrollable, and the cultural was controllable, manageable. And natural resources are free resources, they are something that you take.

Until they are claimed—with borders and states.

Yes. So these historical concepts of nature and culture were political and now we need new concepts to help us govern our environment in new ways. In this sense the technosphere, the Anthropo-sphere are crucial new concepts. The previous ones are useless in the context of governing our environment. What you call today the “ecosystem services”, nature in service to us, is a very old concept of Anthropocentric use of very particular environments. We don’t give them their own agency; we impose our agency on them. And that’s what we are imposing on the whole Earth. Even if you let the forest live its own life, you actually don’t. Because you need it. It’s there for you, not for itself.

Right, because we are a part of it. And this is what you said in your talk during the panel: we are outer space. And we so often displace ourselves from it, again with concepts of the inside and the outside. Maybe it’s because it’s so abstract. What would be the way to bridge our understanding of ourselves and our vital surroundings? Do you have a practice of repositioning?

My personal effort is mapping them, putting them on the map. To map all of these concepts, of the Anthroposphere, the technosphere, outer space, and to examine their critical capacity. What can you do with them? In the context of power relations, governance systems. It is crucial to understand these concepts in abstract ways because they are always abstract and they are used as abstractions by economies and politics. Through our artistic practice we try to contaminate discourse. Politicians have to deal with our concepts. We contaminate economies with our concepts. This idea of open systems, open source technologies, it’s a contamination from the bottom-up.

And it’s incredibly radical resistance. Making anything free. And making anything truly communal is so radical today.

Yes. In this sense, contamination, from externalised to internalised imaginaries, is our strategy.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.