Agency, (Every)wHERE?

Agency, (every)wHERE?’ is a reflection on the works of Amos Peled, presented and performed at FIBER Festival 2024, as well as the illuminating interview they conducted with him. Grounded in a critique of the cartesian and Vitruvian assumptions upon which modern science is founded, von Moltke’s text is an invitation to question the ways in which we use and develop technologies to pacify the ‘objects’ we seek to understand.

Phantom Limb, Amos Peled at FIBER Festival 2024. Photo: Pieter Kers

First Encounter

This writing may best be received as a stream of thought reflection, inspired by the surge of artists and theorists composing novel technologies and ontologies with the intention of grounding our species’ way of knowing in and of the natural environment we seek to understand. At the core of these works is the act of attuning our senses to the communicative signals from the ‘objects’ we have deemed static and inert, by devising new modes of translation. From a place of deep gratitude and admiration to those who have inspired within me this profound desire to respect and listen to the expressive bodies we have labelled ‘objects’, I would like to humbly give my hand at contributing to this critical perspective. Reflecting on the works of Amos Peled, presented and performed at FIBER Festival 2024, as well as the illuminating interview I conducted with him, I invite you to critically put into question the ways in which we develop and use technology to produce knowledge in the name of science.

Agential Assumptions – Ideals

As I sit on my desk tip tapping away, there are two objects intently by my side; the first being a black, cast-iron teapot - a body and vessel of diffusion, an enabler of merging states. As an undisputed object of manifest solidity, it sits on my desk, stubborn and uncompromising, suspended by a plate of the same bonded flesh. Secondly, my turquoise-glazed ceramic mug, moulded to the shape of hugging hands, gives space to the tea kept warm by the pot which carries and feeds. It exists in an unending commitment to hold and be held. One might see these objects as passive things, handled by me, the subject, with my flailing limbs. This would, however, be a sad continuation in a lineage of reductive object/subject determinisms. Each morning, the pot, the mug and myself are equally a part of an interactive ritual.

Central to this reflection is Bruno Latour’s theory on ‘The Parliament of Things’ - “a democracy extending to things themselves”.[1] Latour employs the term ‘quasi-object’ to attribute the objects we too often pacify with a form of agency. ‘Quasi’ implies an overlooked characteristic, as if we have supplanted the nuanced liveliness of things with their silhouettes. Objects are made redundant if not thought of relationally; the pot and mug on my desk are rather trivial, silly things if not contextualised in the union through which they also guide my movements. I must boil water and prepare the tea leaves before I even think to touch the pot. These quasi-objects are thus not slaves to the subject which uses them, as they invoke in me the desire to engage with them and to do all which must be done before entering the union. I move around them, in mind of them, and finally with them. The world consists mostly of such quasi-objects, which exist as nodes in networks ever in flux.[2] The ‘parliament of things’ is Latour’s vision of a politics in which quasi-objects are represented and of a science-practice infused with such a democratic ontology.

Modern science, Latour argues, is synonymous with a specific use of technology and narrativisation of it; scientists use their instruments in order to ascertain facts in nature which presumably exist independent of their discovery. The technologies used are thus framed as tools of purification, whereby phenomena are smoothly, hygienically and with no distortions translated into words and numbers.[3] Notice here my inescapable use of the word ‘translation’, implying a conversion of meaning via a mediator into a different set of communicative signs, because that is precisely what science does, just without acknowledging the limitations of the technology employed and without holding the scientist’s personhood accountable for the assured distortion they are responsible for.

In her stirring work Power and Invention: Situating Science[4], Isabelle Stengers argues that the modern scientist must artificially incubate the work they conduct, in order to create an island, often in laboratory form, of objectivity, surrounded by a sea of representations. This island is a space in which the scientist can slip into an occupational costume, rendering their subjective self invisible, and in which they are given the legitimacy to speak on nature’s behalf. Their technological limbs are thus exercised for the purpose of supposedly smoothening the process of translation without transformation.

The cemented knowability of the world under a microscope is rooted in cartesian dualism; the 17th century French philosopher, René Descartes, radically distinguished between material and mental, body and mind. All human bodies, like those of animals and plants, are ‘spatially extended’ and exist, according to Descartes, in stark contrast to the unbounded nature of the free floating mind. He argued that the properties of substances in the material world are deterministic and predictable and thus operate mechanistically. Coupled with mental properties, certain objects may be puppeteered, according to the distinct laws of the machine's operations, which he claimed takes place in the pineal gland in the brain.

Of key importance for the Western ontological trajectory was Descartes’ belief that humans alone possess both material and mental properties and that god alone possesses only mental properties.[5] All else merely exists in the realm of objects, with no possibility of accessing a mental, subjective experience of reality. With divine privilege, humans may thus be the self-proclaimed mechanics of this world; the fixers, the designers, the knowers, the beings which think and feel and reign supreme.

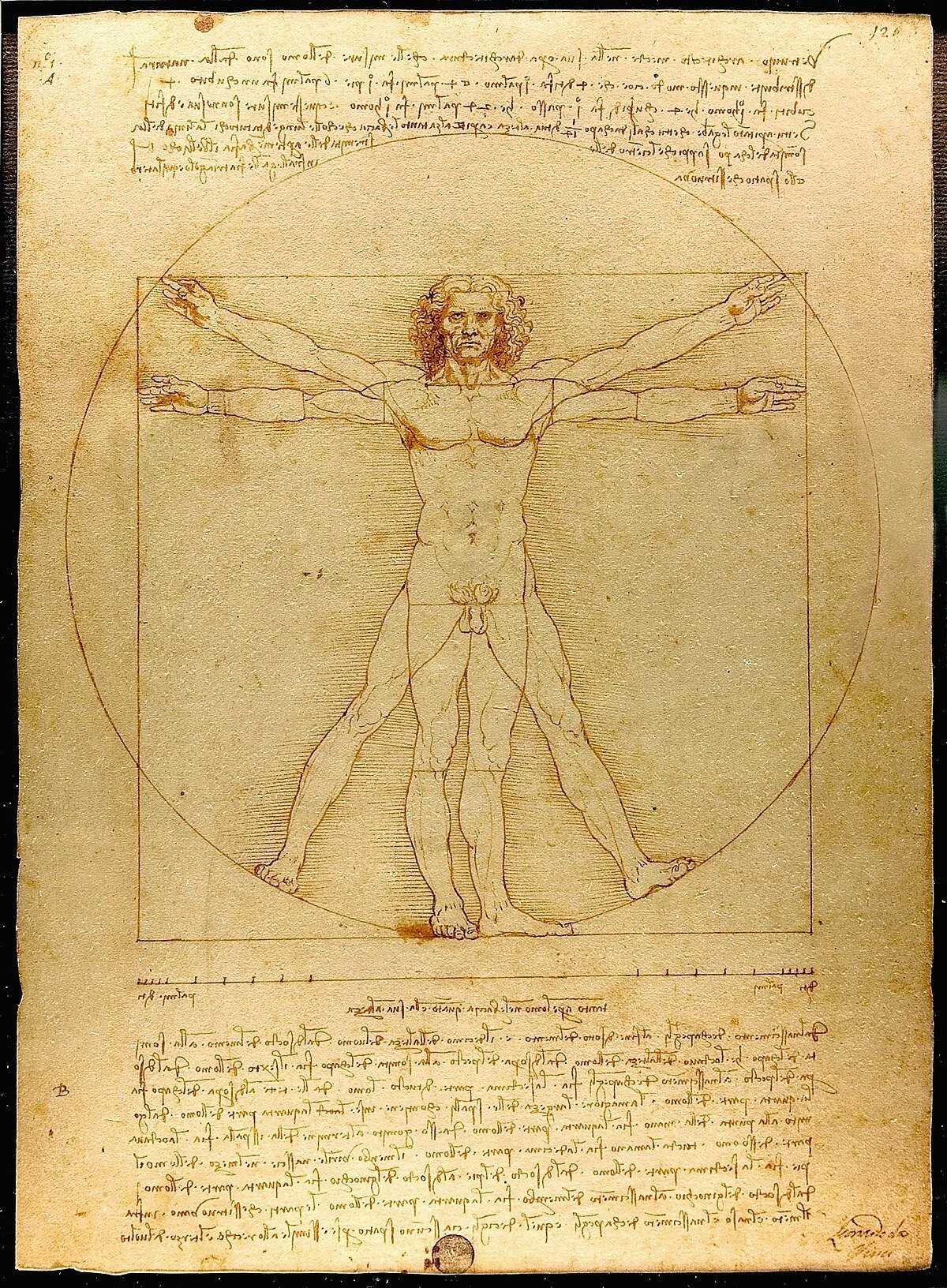

Although the origins of the mind/body dualism are most often traced back to Descartes, its sentiments predate him; the emblematic ‘Vitruvian Man’, drawn 150 years prior by renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, raised the human body upon an unattainable pedestal for centuries to come. A nude man, arms and legs outstretched, inscribed in a circle and square, represents the intersection of the divine and the earthly. The drawing foregrounds the belief that the human body is a reflection of all order in the universe; a divinely symmetrical form; a blueprint for architectural design. Etched into da Vinci’s idea of the human body are proportional measurements with precise ratios, like that of the fibonacci sequence. Having decided which proportions and which sex comprise the divine beauty bestowed upon us by God, he disregarded most if not all bodies, as imperfect as they are. Severed from context, in which bodies move, scar, decay, grow and die in no particular order, this drawing laid the grounds for the Western scientific method—to measure is to know. Moreover, upon being cemented as an archetypal image into modernist conceptions of Renaissance art, the ‘Vitruvian Man’—the ideal body—cast a mould against which all beauty must be measured and in the shadows of which all its animate counterparts may live.

Vitruvian Man, Leonardo da Vinci (Luc Viatour, 2007)

Extending beyond that which we commonly consider to be inanimate, Descartes’ objects monopolise the biotic systems of which human bodies are a part. It is under this pretence that scientists and engineers develop technologies with which we chip away at the gap between our defective bodies and the ideal—the Vitruvian Man. In consequence, as Anne Balsamo contends, we develop a “body awareness [which] is technologically amplified such that we know not only what we do but also how, why and with what consequences”.[6]

She further argues that it is the visualisation techniques integrated into modern technologies, specifically those developed and mediated by scientists and medical practitioners, which justify and perpetuate the surveillance of one’s own objectified body. To know one’s body is consequently made dependent on the mediators of the technology; one can no longer trust in the sensuous human experience as a legitimate source of knowledge. Moreover, there is little space to doubt the legitimacy of science-backed knowledge, as it has constructed itself to be, as Donna Harraway remarks, “a culture of no culture”.[7]

The Grey Space – Oscillations

Amos Peled’s performance of Phantom Limb during FIBER Festival 2024 inventively explored alternative uses of an ultrasound machine, as a means of democratising medical technology and engaging in new modes of translating bodily phenomena. The short, tattooed, scruffy Peled stood half-nude on stage in front of a large square-shaped projector hanging from the ceiling. Sitting in the front row, I couldn’t help but notice that there was no circle, no divine, upon which his body was impressed; he existed wholly in earthly form, imperfectly asymmetrical. By his side was a rather outdated looking ultrasound machine, out of which extended an umbilical cord with a transducer on the end.

Medical ultrasound machines send pulses of sound into our bodies which are reflected back as echos upon making contact with tissue. The time it takes for the echo to be received, as well as its strength, determine the grayscale imagery. In effect, this machine is one of translation from biotic material to sound waves to analogue imagery. Sonographers must thereafter interpret the moving images to make diagnoses.

Frequently gelling the transducer, Peled began pressing and rubbing it against various body parts. Beginning with his kidney, the projection lit up into a grey seascape with gentle waves ebbing through his ribcage and across the room. The force of a soft current coursed its way between the audience and the performer, as the sound of the rippling echoes stuttered its way through the machine. Moving up toward his heart, the white noise, the steady silence of contact, started bouncing, thudding—his head bobbed and his body swayed. As his drumming heart fastened and loudened so did his body, letting it carry his movements, dancing to the rhythm of his heart. Where does the agency lie here? May the fluctuating pace of the beat be the sonic reflection of the dance between him and his heart, differentiated but entangled?

Peled grew up spending much of his time in hospitals, wired to technologies, strung up in medical opinions. During our conversation, reflecting back on this time, he expressed to me the alienating feeling of being subject to inaccessible technologies and fearful interpretations. At the age of 19 he decided not to return to the hospital, as it made him feel sick relative to the doctors’ ‘idyllic form’ of health.

Feeling better in the years to come, Peled’s time in the hospital stirred within him a gnawing curiosity toward the technologies he knew all too well and not at all. Having obtained from an auction his first ultrasound machine to explore his body on his own terms, he practised novel methods of listening to his organs, all the while feeling stimulated in the act of appropriating the technologies which had until then been gatekept under the guise of the scientific method. In conversation on his relation to technology in the hospital, he expanded on the objectification of bodies:

“To test the body with technology, you have to look at the body also as a technology, as some sort of input output. You have to use an idea or some sort of goal - let's call it ‘healthy’ - which is in itself already an abstract concept. If you are a doctor or you want to treat someone, you have to use some sort of idyllic form, which is fixed. Is ‘healthy’ someone that has two hands or someone that is symmetrical…?

I find this very problematic but at the same time working in such a place like the medical environment, you have to be efficient, you have to be very precise and concrete. But there is some sort of grey area and that is what I’m interested in.”

The grey space is a landscape of shifting representations and interactions—a playground for negotiation. Peled’s performance, like those of doctors, is a narrative on the human body. However, what distinguishes the two is that Peled’s grey space does not impose upon the quasi-objects within his body a strict will, a diagnosis. He poetically chooses to analogise his organs to various biomes (oceans and forests), whilst welcoming that which remains unfamiliar in its perennial state of becoming. The transducer making contact with Peled’s skin resonates the sound of a gusting wind, immersing the room in his body’s ecosystem. His body’s singular, unified form was made unstable; his organs conversed with him and through him, producing a myriad of voices, all etching out their agency in the grey space the technology provides.

Phantom Limb, Amos Peled at FIBER Festival 2024. Photo credit: Alex Heuvink

Peled’s unashamed indulgence in the representational deformities of the ultrasound machine shifts the narrative of the body from a “thing of nature” to “a sign of culture”.[8] He imbues the machine’s sounds and images with personal quirks, such as distortions in the sound to make them more ocean-like. In doing so, he produces knowledge of the body through his personal relation to cultural conceptions of identity, beauty and health; as cultures mutate, so do our bodies. This is not to say that the grey space should be disregarded as being purely subjective, purely cultural; it exists in the space in between. Just as our politics have in recent decades been interjected by the moving, reactionary earth, so have Peled’s representations. The frame of reference may be a reflection of the artist’s subjectivity but the pulsing, throbbing, thudding, and ebbing remain untamable. Freed from the ideal, the body and our representations of it may unceremoniously oscillate between development and decay. This unending tussle between agential forms of intelligence for representational space is well explained in Nature’s Queer Performativity, as Karan Barad alluringly writes:

Differentiation is not merely about cutting apart but also cutting together (in one movement). Differentiating is a matter of entanglement. Entanglements are not intertwinings of separate entities but rather irreducible relations of responsibility. There is no fixed dividing line between ‘self’ and ‘other’, ‘past’ and ‘present’ and ‘future’, ‘here’ and ‘now’, ‘cause’ and ‘effect’... Cartesian cuts are undone. Agential cuts, by contrast, do not mark some absolute separation but a cutting together/apart– a ‘holding together’ of the disparate self…[9]

Ascribing agency to one’s cells, organs, tissue is not a form of rigid estrangement, but of entanglement. When Peled pressed the transducer up and under his chin, tucked into his throat, the grey space was split in half by his fissuring vocal cord. Upon swallowing and grunting, the two halves on screen neurotically convulsed and contracted; with each throttle, Peled jolted his head from side to side, as if his internals were arguing, nagging each other, using him, the mediator, as a tool for representation.

Access to the performance (of the grey space) seemed democratically diffused amongst the many selves which comprised the disaggregated body we saw on stage. In this sense, the body, like my unionionised tea set, is a relational network of interdependent entities/bodies, entangled through their ongoing quarrels and alliances. An artistic or scientific practice departing from an acceptance of difference will thus employ technology with the intention of conversation, debate and mutual questioning; things may reject your questions, disagree with them, or generate new ones.[10]

Boundary Work – Entangled Disciplines

My intention is not to diminish the role and value of science but rather to open it up to the possibility of letting the phenomena we study put our categories and identities into question - to use technology in a way that is sensitive to feedback. Artists such as Amos Peled and theorists such as Bruno Latour, who have in different ways surrendered the presumption of anthropocentric agential domination, in favour of an open field of mutual responsibility, are steadily growing and inspiring new modes of technological mediation. They are working on the boundaries—the spaces in between disciplines and systems of knowledge—by repurposing and reconstructing the technologies which have been used to reify absolute differences between fields.

Barad’s theory of “differentiation [as] a matter of entanglement”[11] may be applied to the entanglement of disciplines; the compulsive need in modern science for objectivity insulates it from the truths to be found in artistic practice. The unyielding ‘cuts’ of the cartesian and Vitruvian kind - those denying the forces of entanglement - leave calculated scars on our bodies and minds. These ‘cuts’ are, in effect, cultural inscriptions on bodies labelled as ‘natural’. An entanglement of differentiated disciplines may open facts to the influence of truth—science to art. By interacting in the technologically mediated grey space between culture and nature we may recognise, respect and listen to the agencies of unsuspecting bodies.

Notes

[1] Bruno Latour, 1993, p. 142.

[2] Massimiliano Simons, 2017. “The Parliament of Things and the Anthropocene: How to Listen to ‘Quasi-Objects’.” Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 21(2), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.5840/techne201752464.

[3] Bruno Latour, 1993.

[4] Isabelle Stengers, 1997. Power and Invention: Situating Science. University of Minnesota Press.

[5] Robinson Howard, 2023. “Dualism.” In Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

[6] Anne Balsamo, 1996, Technologies of the Gendered Body. Duke University Press.

[7] Donna Harraway, 1997, “Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium. FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouseTM.” Feminism and Technoscience. Routledge, p. 25.

[8] Anne Balsamo, p. 3.

[9] Karen Barad, 2012, “Nature’s Queer Performativity*.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.7146/kkf.v0i1-2.28067, pp. 148–149.

[10] Simons, 2017.

[11] Karen Barad, 2012, pp. 148–149.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.