Upset-Minded Bodies Coded as Absent Agent Mindsets (Part One)

Ping-Ponging Between the Mechanical Teeth of the Big Hungry Wolf

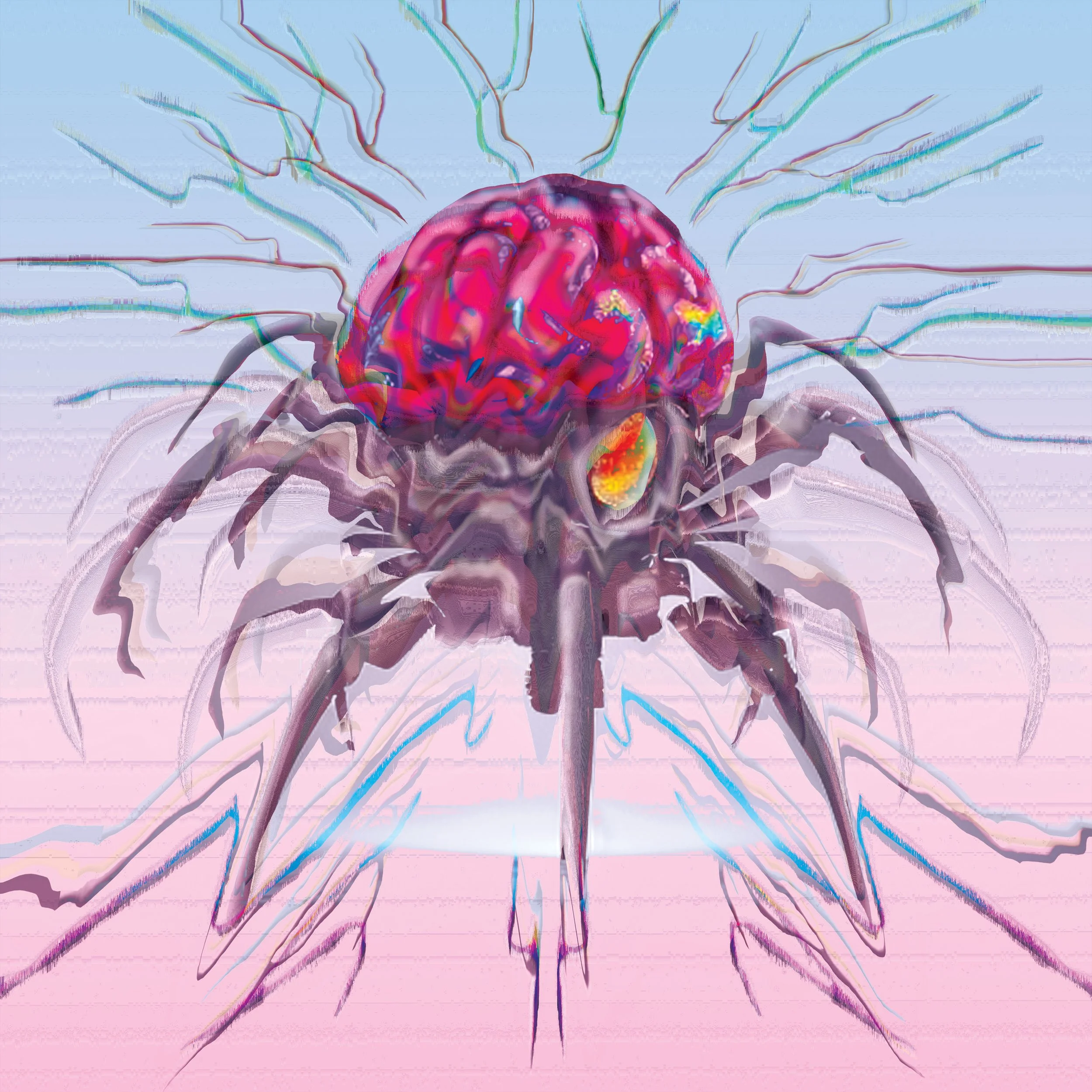

In the age of technocapitalism, bodies and minds are constantly subjected to a cycle of alienation and disempowerment. The first part of Babak Ahteshamipour’s essay explores how cyberspace, once a refuge for marginalised bodies and alternative identities, has been commodified and colonised by capitalism, reducing it into a sterile and regulated environment. Using concepts such as countergaming, playbour, and prosumerism, Ahteshamipour examines how digital spaces and video games offer both a means of reclaiming agency and a site for capitalist exploitation. From mods and machinima to the fractured identities projected across platforms, the essay highlights how marginalised individuals use cyberspace and gaming to resist societal norms and reimagine their identities in a system that continually seeks to control and monetize them. Yet, even these spaces of resistance are increasingly co-opted, as capital repurposes tools of rebellion into commodified forms of labour. Ultimately, the essay questions whether true escape from the capitalist system is possible, or if it inevitably haunts even the most resistant corners of cyberspace.

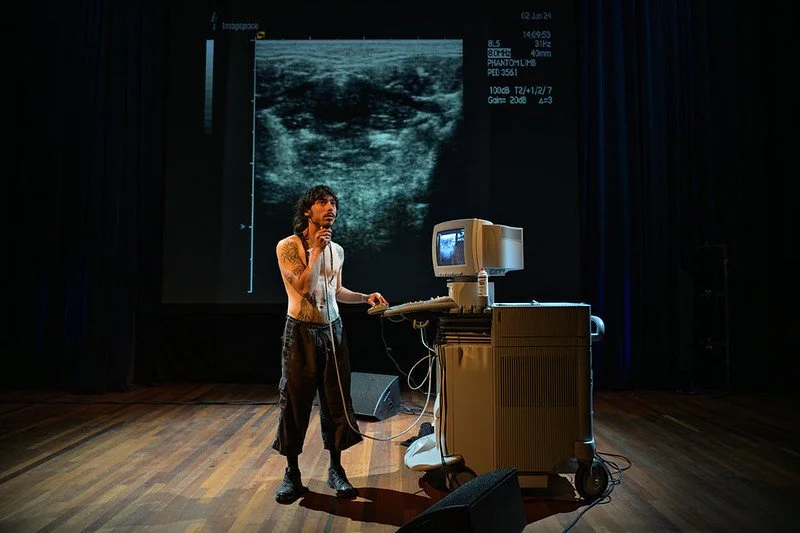

On January 19th 2024 the band Glass Beach released their album Plastic Death. The track entitled Motions resonated with me deeply due to its lyrics which describe the grinding mode of technocapitalism, and the breakdown that hits at 02:30 mark with the vocalist screaming “I wanna find” that reminded me of the times I scream in my head out of desperation, for not finding alternative “survival modes” outside of capitalism while my body’s resisting to integrate within it. This specific passage of the lyrics hit me hard:

“going through the motions

i wanna be the new routine

i wanna kill the competition

and i wanna run like a machine

i wanna find another way out

select all images containing traffic lights.

select all images containing stop signs”

Departing from this passage, I started thinking about the amount of time that I have spent escaping within cyberspace to avoid this profit-driven sterile and violent reality, desiring to reclaim the agency of my own body by seeking alternative realities. Secondly I realised that capitalism will always haunt you to the edge of the Earth, or in the sake of this essay, to the edge of cyberspace. The infiltration of platform capitalism within cyberspace has murdered its diversity, leaving digital ruins in its way and transforming it into a deserted Arrakis. The Imperial House in this metaphor is technocapitalism and the culture industry which have commodified cyberspace through censorship, surveillance, monetisation and enshittification[1]. This reminded me of the dead internet theory[2]: most of the internet is devoid of living users and is instead is colonised by bots, generated content, AI language models and algorithms. Although a conspiracy theory I find it relevant to the contemporary reality of the internet.

Cyberspace was the rooftop of the other, the marginalised and displaced body, the outsider, where one would find refuge under the guise of avatars, emoticons and emojis, pseudonyms, anonymity, in virtuality, in fictional worlds and lores, digital graphics and 3D models, online niche forums, blogs and chats. It was a virtual cybertopia where a body that drifted away from the mainstream discourse would automatically seek shelter. But what is it to be the other? To be on the outside? Not being able to fit it within pre-constructed engineered structures of power, identity, desire, gender, sexuality and role playing? To be longing for alternatives? To desire to live life otherwise?

Otherness stands as secondary to the big Other, the big daddy wolf, the Symbolic order, the name of the father, the mainstream capitalist discourse that tries to superimpose itself on everything and everyone, the laws that control and engineer desire, the marketing tools that calculate libido. By not following the Other — or being consumed by it —, one drifts away and becomes-other[3], acquiring new experiences of reality, separating themselves, becoming-alien to the social standards of what an acceptable and valued person is. Within algorithmic culture the agency of a body is moulded, hammered and designed by a multiplicity of Selves which emerge on interfaces of computer technologies: video game avatars, social media profiles, blog and forums accounts, emails and server profiles. Computers become machines of “subjectivation”.

Once in cyberspace we re-individualise, our Self is sliced into micro-identities[4] based on which platform we are on, which game we’re playing and so on. Our body is projected within algorithms, scattered across forums, blogs, social media platforms, video game avatars, and servers. Algorithms and machines segment us into distinct alts and platform-specific identities.[5] Don Ihde writes in Bodies in Technology:

“We are our bodies-but in that very basic notion one also discovers that our bodies have an amazing plasticity and polymorphism that is often brought out precisely in our relations with technologies. We are bodies in technologies.”[6]

The Counter Esc

Two of the most prominent places where marginalised bodies and identities find their ways are the Internet and video games. The internet was never intended to be the shelter for niche diverse cultures; it was originally a military project funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (Arpa) – later named Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa). Ben Tarnoff writes in How the internet was invented:

“As a military venture, Arpa had a specifically military motivation for creating the internet: it offered a way to bring computing to the front lines. In 1969, Arpa had built a computer network called Arpanet, which linked mainframes at universities, government agencies, and defence contractors around the country. Arpanet grew fast, and included nearly 60 nodes by the mid-1970s.”

However the Internet was officially launched on August 6th 1991[7] and the first search engine NCSA Mosaic 1.0 in 1993[8]; despite its military roots, it soon became a diverse home for the niche, outsider and marginalised voices. Internet culture was born, Tumblr popped up and became a space of expression for LGBTQIA+ communities with blogs that featured explicit and sex positive content[9] alongside other bizarre blogs such as Godzilla Haiku, Citation Needed or Awkward Stock Photos, Reddit became a gathering inn for academics in sub forums discussing Lacanian psychoanalysis, feminism, materials science or astrophysics. Fandom and internet aesthetics occurred as alternative cultures with their own lores and nerdy systems that remain outside the mainstream discourse with examples of The Torture Soup or the BEN Drowned creepypastas or fictional characters such as The Slender Man or places such as The Backrooms. Memes drew criticism on the status quo through satire and irony and were primarily hosted on user-generated content platforms such as 9GAG or imageboard websites such as 4chan and hacktivists found a ground to connect, collaborate and engage in creating organisations such as Wikileaks and the Anonymous which share common concerns regarding information-hoarding.[10] The Internet became a decentralised system that cancelled the gatekeeping of knowledge, information and assets; Hussein Kesvani writes in A Brief History of Internet Culture:

“In the late 90s and early 2000s, the internet was structured on the basis of decentralisation. There’s no better example, in the West, than music sharing. In 1999, there were many speculative claims about a piece of software called Napster – the first “peer to peer” music sharing service, where anyone could download any piece of music they wanted. [...] Softwares like KaZaa, Bittorrent, Limewire and Emule were all constructed off the back of peer-to-peer file sharing, providing a near endless supply of music, movies, television, and comic books that could be accessed with a few clicks of a mouse.”

Artists with interests unrecognised by institutions forged communities and found spaces within Tumblr and other platforms that hosted digital art such as Rhizome, Breed and Nettime and communities such as DeviantArt and Conceptart.org[11] Within the interne a minor literature was born in terms of what Deleuze and Guattari define as minor literature: “minor literature does not come from a minor language, it is rather that which a minority constructs within a major language”[12],— which in the case of this essay is within the discourse of the big Other.

Video games also offered worlds for the diverse and niche as means of algorithmically reclaiming agency over their body through counterplay, experimentation, failure, and gender exploration by subverting video games engines. Counterplay is a term coined by Greig de Peuter and Nick Dyer-Witheford[13]; Alexander R. Galloway calls it countergaming[14]. Countergaming repurposes games for alternative desires; it dismisses the normative structural logics of a game and transforms it into a domain for finding potential alternatives of identity and agency.

The most predominant examples of countergaming would be modding, machinima making and hacking/glitching. Modding (short for modification) is the activity of creating and importing custom-created scripted content within existing video games in an attempt to alternate aspects of it.[15] These mods can be supplementary or can result in an entirely new game, which is then called a total conversion. Major historical examples of total conversion are Counter-Strike which was originally a multiplayer mod for Half-Life (1998)[16] and Defense of the Ancients (DOTA) which was a Warcraft III game mode developed with the Warcraft III World Editor in 2003.[17] Alexander R. Galloway defines three ways that a video game can be modified:

“A video game may be modified in three basic ways: (1) at the level of its visual design, substituting new level maps, new artwork, new character models, and so on; (2) at the level of the rules of the game, changing how gameplay unfolds — who wins, who loses, and what the repercussions of various gamic acts are; or (3) at the level of its software technology, changing character behavior, game physics, lighting techniques, and so on.”[18]

Machinima (machine + cinema) is the use of existing video game engines to create artistic videos or movies. The movies feature a wide range of practices such as avatar performance or scripted bot performances or captured footage that is edited in post production. A predominant example of machinima would be the Red vs Blue Halo machinima series (2003 — present) or the Leeroy Jenkins machinima (2005). Machinima creation can be considered a development of critical content within mainstream games; as an attempt of resisting commercial media industries by creating a stand-alone culture with its own means of production and distribution.

Some other practices of countergaming include speedrunning — playing games at accelerated speed by taking advantage of glitches and design flaws drastically altering the game’s temporality and spatiality — and slow walking — exploring aesthetic, audiovisual, and environmental details of the virtual spaces found within games. The alternative temporal and spatial movements within games embody alternative desires as well such as the desire to be hasty or to slow down.

In-game counter-practices that are temporal based resist chrononormativity as emphasised by Bo Ruberg[19]. Chrononormativity is a term that is associated with queer studies of time, coined by Elizabeth Freeman; it is the set of expectations that dictate how individual lives and larger historical narratives should progress, normalised and banalized logics that dictate what one should do, where, when, and at what speed.[20] Be a good child, go to school, be a good student, graduate, get into university, graduate again, get a job, get promoted, find a partner, marry, have kids, make more money, retire, grow old and die.

This chrononormativity is imposed on video games as well, how much time you can be at a certain level or have a certain buff, where you can be at which level, restrictions in time, space and movement, in the sense of how Foucault pointed out within disciplinary societies that institutes regulate the movement of a body within physical space threatened by authoritarian punishment[21] — which in gaming vocabulary that would translate into a game master banning you from the game.

Video game music is anti-chrononormartive as well, as proposed by Tim Summers in The Queerness of Video Game Music, in the sense of how music composed for games doesn’t incorporate high-end technologies of its time, doesn’t follow mainstream musical genres and qualities of its era, and features non-linear compositions. An example of that would be the 8-bit electronic music of Undertale, chiptunes and the looped music that plays in the background zones of open world game zones. But in general video game music tends not to be focused on one genre, rather blends and draws elements from many different genres from different eras such as the example of Final Fantasy XIII’s original soundtrack or Panzeer Dragon’s original soundtrack that ranges from classical music to ambient and from electronic to jazz fusion.

Despite the fact that LGBTQIA+ community has been underrepresented in video games, they “have long offered invaluable opportunities to explore gender, sexuality, and identity in ways that may not have been possible outside of games''[22]. Avatar customisation and gender choices within games can be a vicarious experience of gender for queer folks. As Jessica Janiuk writes in Gaming is my safe space: Gender options are important for the transgender community:

“Games like The Elder Scrolls, World of Warcraft, Mass Effect, Dragon Age, Second Life, and any other game that allows character creation with gender choice give us the opportunity to be seen as and interact with the world as the gender to which we identify.”

Gaming culture is often misrepresented in mainstream media as the domain of hardcore gamers: white, cisgendered, heterosexual, able-bodied boys with a heavy emphasis on skills. Today studies show that nearly as many women play video games as do men and 1 in 5 active gamers are LGBTQIA+;[23][24] Gaming culture, however, continues to be dominated largely by the voices of hardcore gamers. The gaming industry itself after all has always been addressed towards hardcore gamers, positioning the rest as “secondary other”, in a hauntological sense, but this is starting to change with the more inclusive representation of female and LGBTQIA+ voices within gaming culture as underlined by Keza MacDonald in the article Meet the gaymers: why queer representation is exploding in video games:

“Aside from representation within games themselves, the way that communities gather around games has also been a driving factor in changing the state of play: queer gamers – or gaymers, as many playfully identify – are more visible too. Discord chat servers, Twitch streaming and of course social media have brought people together and created sub-communities where queer players find each other.”

I’m Disarmed & My Weapons Are Sold Back to Me

Gaming involves not just playing within worlds but also producing them. Besides the game designer’s roles in producing them, the inclusion of editing tools in games as a marketing strategy to exploit the rise of modding and machinima culture, and a drive toward user-generated content creates a commodified dimension of resistance. Relevant to this phenomenon is the so-called playbour (play + labour), coined by Julian Kücklich in 2005 in the article Precarious playbour: Modders and the digital games industry. Playbour encounters anything that takes place within digital games as a form of play, and “therefore a voluntary, non-profit-oriented activity".

Another relevant term is the term prosumer (producer + consumer) coined by Alvin Toffler in the book The Third Wave (1980). The prosumer produces content out of already existing commodities. Media produced within and through video games, or even the game itself is neither a result of the developers nor the game players; rather input from both players and developers is required in their production as emphasised by Sue Morris in WADs, Bots and Mods: Multiplayer FPS Games as Co-creative Media.

In hyper-capitalism, the culture and tech industries provide new instruments for media productions within their own products, thus capitalising the means that once were reactionary towards itself and transforming into exploitative labour. After all “capital gets some of its best ideas from the resistance it provokes”[25].

All illustrations are made by the author.

Notes

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/pfie.2011.9.1.138

Don Ihde, Bodies In Technology, 2002, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, U.S.A., p.138

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.11537055.35?seq=12

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-rise-fall-internet-art-communities

Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter, Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games, 2009, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, U.S.A., p.191

Alexander R. Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, 2006, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, U.S.A., p.124-125

https://blog.acer.com/en/discussion/574/video-game-modding-what-it-is-and-how-to-get-started

https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2017/05/does-valve-really-own-dota-a-jury-will-decide/

Alexander R. Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, 2006, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, U.S.A., p.107-108

Bo Ruberg, Video Games Have Always Been Queer, 2019, New York University Press, New York, U.S.A, p.184-191.

Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Historie, 2010, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, United States, p. 3-4

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison second edition, 1995, Penguin Books Ltd., London, U.K., Translated by Alan Sheridan, 1977, p. 130

Bo Ruberg, Video Games Have Always Been Queer, 2019, New York University Press, New York, U.S.A, p.4

https://www.theesa.com/resources/essential-facts-about-the-us-video-game-industry/2024-data/

Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter, Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games, 2009, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, U.S.A., p.11.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.