Floris Vanhoof’s “Antenna”: Snaps, Crackles, Hums, Noises, Bleeps, and Pulses

In this interview, Katažyna Jankovska talks with the artist Floris Vanhoof about the presence of electromagnetic waves, invisible phenomena, and his latest work, “Antenna,” which features a grand piano set on its side with a hexagonal antenna on top, presented at this year’s FIBER Festival.

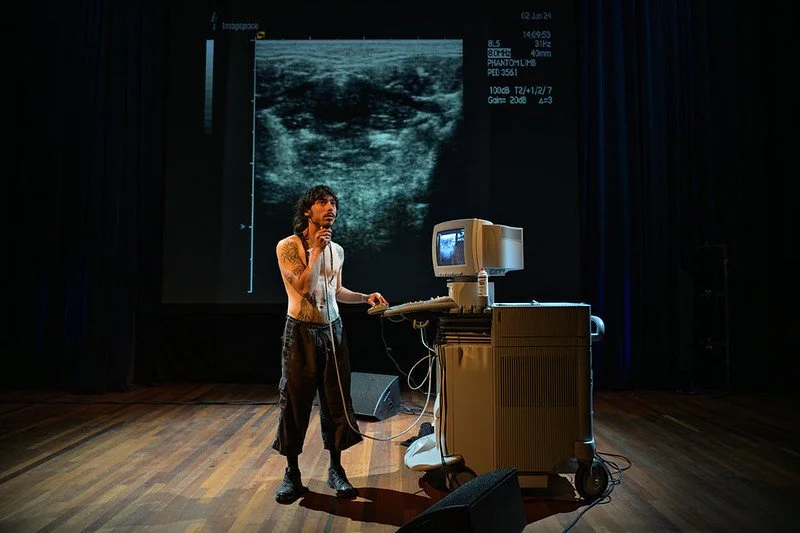

Floris Vanhoof, “Antenna” (2024). Neighbouring Frequencies exhibition, FIBER Festival 2024.

Photo credit: Carmen Vollebregt.

There is a network of signals constantly permeating our spaces and bodies. These signals originate from communication satellites orbiting in outer space, telecommunications networks, wireless devices like smartphones and computers, microwaves, surveillance systems, and public transport infrastructures, among others. All of our bodies are bathed in these waves. They form electromagnetic fields that, though invisible and largely unnoticed, are omnipresent, enabling the functioning of modern society and shaping the environments we inhabit.

While most of these electromagnetic fields are man-made, the Earth also produces its natural electromagnetic resonance at extremely low frequencies. Long before humans harnessed electricity and radio waves, these natural emissions were already present in the atmosphere. They are born from phenomena like lightning strikes, Earth's magnetic field fluctuations, cosmic radiation, and auroras triggered by solar storms like the aurora borealis and aurora australis, which can result in the emission of radio signals.

Though different in origin, these two types of waves coexist in the same physical space, sometimes intersecting and influencing each other in subtle ways. Each electromagnetic wave has its own unique signature, imperceptible to the naked human ear but adding to the rich, invisible symphony of sounds that fill our environment.

Many artists are intrigued by the presence of electromagnetic forces manifesting themselves in our everyday space. Through demodulation and amplification, these hidden fields can be detected and transformed into audible soundscapes, offering us a glimpse into this otherwise inaccessible dimension. To mention a few, Christina Kubisch’s “Electrical Walks” with specially developed earphones, which translate electromagnetic waves in the city into acoustic signals, or Catherine Richard’s “Shroud/Chrysalis,” where visitors cloister themselves away from magnetic waves by stepping inside a Faraday cage, a metal enclosure that blocks electric fields and electromagnetic waves.

Belgian artist Floris Vanhoof explores this realm with his piece “Antenna.” Vanhoof is an Antwerp-based filmmaker, musician, instrument builder, performer, and visual artist who translates one medium into another to investigate how our perception operates. By crafting his own instruments and combining media that are often incompatible, Vanhoof challenges our patterns of perception and reveals new ways of seeing and experiencing the world.

One of his latest works, “Antenna,” presented at this year’s FIBER Festival under the theme “Outer/Body,” embodies the festival's exploration of the connections between bodies and the environments they inhabit. The work features a grand piano set on its side, with a hexagonal antenna mounted on top. While detecting electromagnetic waves, small electromagnets make the strings of the piano vibrate. This sculpture, placed in one of the rooms of the Flemish cultural centre de Brakke Grond, acts as a massive receiving device, detecting the electromagnetic waves that permeate the space, questioning the boundaries of our bodies and systems that interconnect us. The piano converts these frequencies into sound waves, allowing visitors to hear the electromagnetic phenomena that usually go unnoticed.

The sounds produced by “Antenna” are site-specific, varying in tone and volume depending on the location it is presented—each space offering a different auditory experience. Yet, despite these variations, one common thread runs through them all—the ubiquity of electromagnetic waves, present even in places where they are least expected.

Although these signals come from different sources, including streams of conversations and media, Vanhoof’s work does not treat these frequencies as mere carriers of information but rather presents them as carefully selected soundscapes filled with whistles, hums, and thuds. By capturing and translating these frequencies into audible form, Vanhoof invites visitors to become aware of the invisible electromagnetic systems that interconnect us all, revealing the intricate relationships between people and the technology embedded in their daily routines. Through this work, Vanhoof seeks to make the unseen, seen—or rather, heard—reminding us of the vast, invisible world that exists just beyond our perception.

Floris Vanhoof, Antenna (2024). Neighbouring Frequencies exhibition, FIBER Festival 2024.

Photo credit: Carmen Vollebregt.

Your artistic journey started with film. You studied experimental cinema in Brussels and your first projects involved 16 mm celluloid experimental films and slide installations. What led you to shift your focus toward sound in your practice?

I discovered that sound, like film, is a form of projection. This idea of projecting sound inspired me. In 2018, I created an installation called “Talking Gongs,” which features two orchestral gongs, nearly a metre in diameter, hanging from trees. They "talk" to each other in a way embodying an animistic idea where I made characters out of them. Although it's just electronics, it feels like they communicate. When the electronics operate fast enough, it becomes pitch; when slow, it turns into rhythm, and they strike the gongs using transducers, similar to the inside of a loudspeaker, creating physical sound.

Another installation from that time is “Polyhedra,” which was created with modular sculptures. I found a way to make modular sculptures using triangles, squares, and pentagons made from cardboard, held together with rubber bands. I made 50 sculptures, most of which hang in the air with a loudspeaker inside. Some are small, and others are as large as a person standing on the ground with a bigger speaker, like a bass speaker, inside them. This work is inspired by the sound of a classical orchestra, where numerous musicians create a rich, immersive experience. I couldn't replicate this effect with live music played through stereo speakers. But using 50 speakers could achieve this. Small speakers produce high-treble sounds differently than large ones. So, if there is a movement from high to low in music, it will also move in space from one speaker to another. With 50 speakers, this effect becomes very exciting to play with.

What sparked your interest in exploring imperceptible phenomena?

I often have to sit on ideas for a long time. I was interested in invisible waves for a long time but couldn't find a way to work with them. Many of my works involve translating one medium to another, and I struggled to find a good medium to translate these invisible waves.

During my first exhibition, I placed a grand piano on its side. The audience could hit the piano with tennis rackets and balls, producing acoustic sounds. I amplified these sounds with guitar pickups and added a short delay so the sound would come back electronically treated, creating a wave-like effect. One could hear both acoustic sounds from the piano and electronic sounds from the back, which I found intriguing both in terms of sound and visual impact.

You never look at the grand piano like that. And I always wanted to turn a piano on its side again. It loses its mechanical function, creating an interesting visual. In the long run, I realised this could be exactly the medium to translate these invisible waves I was interested in. I even made a simple drawing of a grand piano on its side with an antenna on top. At first, I wasn't sure if it would work, but I had a fixed idea of how it should look. This image stayed with me for months, and the project took almost two years to complete.

Let’s talk more about the “Antenna,” with the grand piano on its side, that you presented at FIBER Festival 2024. I read that you got interested in the omnipresence of electromagnetic waves while listening to the radio during a thunderstorm and hearing that the lightning strikes became audible as cracks and pops. How did this experience influence your approach to incorporating electromagnetic waves into your artwork?

I was listening to classical music on the radio during a thunderstorm. I noticed that the sounds on the radio would crackle with each lightning strike. I wondered, what is this? Of course, it's interference in the electromagnetic spectrum. This made me interested in how I can capture those phenomena. I initially thought the electromagnetic spectrum was mainly used for human communication, but a significant part of it also comes from nature. It's really interesting how these two sources interact and interfere with each other.

When talking about the inspiration for this work, you mention Alvin Lucier’s Sferics, an experimental music piece that involves recording natural radio-frequency emissions originating in the ionosphere. Lucier used sensitive antennas and receivers capable of detecting very low frequency (VLF) and extremely low frequency (ELF) waves. By translating these emissions into sound, he allows listeners to hear the "music" of the ionosphere, which is usually inaudible to the human ear. What particularly fascinated you about this work?

In his liner notes, Alvin Lucier mentioned a book about how to make an antenna yourself. He indeed once made recordings of spherics—a phenomenon occurring when things enter the atmosphere. If you're in a quiet place without traffic or other noise, you can hear these sounds with an antenna. He made his antenna for that purpose, and I really liked the sound. Then, I learned how to make antennas myself. I made large crosses with lots of copper wire and started listening to the waves in the air. I could tune into radio frequencies and listen to various sounds in an analog way. However, it was challenging to translate this to the piano because it produced a lot of noise. I realised I needed to avoid listening to a single radio frequency, as you do with a radio station. Instead, I thought the piano, with its many strings, could listen to multiple frequencies.

How does your artwork explore the interaction between natural forces and man-made signals?

The main idea behind the installation is that there are thousands of waves in the room we are in at any given moment. Some go through the walls, some pass through our bodies, and others bounce off the walls, traveling back and forth until they dissipate. These waves travel globally, and I found this concept very exciting. They are used for so many things, including playing classical music on the radio. However, it's fascinating how nature can disrupt these signals.

Imagine listening to a slow classical music piece on a rainy, dark day. Suddenly, the outside environment disrupts the music, bringing the outside inside. This idea is similar to what composer David Tudor explored—using small electronic circuits to create big sounds. It's like listening to your radio with good music, but then something big, like a thunderstorm, interrupts it. So, what is the difference in sound when it comes from a source like a thunderstorm and other big natural processes, compared to something like a phone?

I translate these phenomena. When the antenna receives a wave, it goes into the computer and opens or closes a gate, making the electromagnets work. This action affects the piano strings. I'm not sending the received frequency directly to the piano because that wouldn't work. Instead, I choose the frequencies for the strings.

Floris Vanhoof, Antenna (2024). Neighbouring Frequencies exhibition, FIBER Festival 2024.

Photo credit: Pieter Kers

Can you elaborate on the technical aspects of your installation, particularly regarding the use and selection of frequencies, electromagnets, and the interaction between the piano strings and radio signals?

While developing this work, I was invited by Stuk in Leuven to work on this installation at their art center. Together with one of the doctoral students from the university of Leuven, we hacked a software-defined radio device, enabling us to listen to 22 frequencies simultaneously. This is something a computer can manage but would be impossible for a human. At the same time, I reached out to a professor in London who was experimenting with making piano strings move using electromagnets. I initially tried creating my own electromagnets, similar to an EBow that makes guitar strings resonate, but they weren't strong enough for piano strings. So, together with ordered custom-made electromagnets.

The installation uses 16 electromagnets, each attached to a piano string with its own base frequency. For instance, when a car key signal at 432 MHz is picked up, it triggers a string to vibrate at a different frequency, like 440 Hz. I discovered that not only the string's natural frequency but also its harmonics could be used. I can play four or five different frequencies on each string. By gradually shifting between frequencies, the vibrations travel through the string beautifully.

Each string can pick up different signals. I tune the antenna to 32 frequencies, and each string handles two frequencies, performing tasks like opening a gate or changing the waveform. The strings can be pushed and pulled up to 100 times per second, causing them to resonate. The intensity of this movement—whether gentle or forceful—shapes the timbre, and even at the same frequency, the sound color can vary significantly due to the string's physical response to different stimuli.

You can also see the installation as a composition. I spent a lot of time programming the sounds and discovering things I didn't think were possible on the piano. But all the polyphony, dynamics, and rhythm come from the antennas receiving various signals, making the work almost site-specific. I do not interfere with that. Yet I need to retune the frequencies each time I set it up. I listen to find interesting signals, like those with frequent and dynamic movements, and incorporate them into the installation.

The sound quality is very important to me. The concept needed to sound original and different from a classical piano. The piano is an instrument from the mechanical age, and when you place it on its side, it no longer functions as intended. So, I had to make it work better in this new position.

Were there any interesting findings or incidents while tuning in those frequencies?

Yes, and it was actually very scary. It was the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine when I was experimenting with the antenna, and I could hear Russian voices. It was really frightening. I looked it up through the university of Twente that has an antenna on the roof that you can tune into via the internet. In the chat I read, people mentioned that not all Russian communications are shielded or encrypted, so some can be heard. It was very scary because it made everything feel very real, unlike listening to classical music or natural sounds from the sky.

But there are many interesting channels. For example, in Leuven, I could easily listen to the traffic tower at the Brussels airfield because of its proximity. However, I don't use the actual content of the pilot's communication in the installation. Instead, I use the noise barrier that occurs when the pilot speaks. I set a threshold above that noise barrier so that when contact is made, the gate in the computer opens, and the string starts to vibrate. That's how I played with that.

Can the viewers distinguish or recognise those sounds and their sources?

No, I'd like to leave that to the imagination. I usually present “Antenna” in a dark room with just a few spotlights and a bench to sit on. I could be very specific and use a screen to indicate each sound, but that would take away from the artistic and musical experience. I prefer to leave it to the viewer's imagination. In my studio, I spend a lot of time deciding what to show and what not to show. Finding an equilibrium often enhances the work.

Do you have any plans to further develop or modify this artwork in the future?

It's very exciting to show this work in different places. A few months before Amsterdam, I showed it in Münster and Düsseldorf. The work is always different because I'm tuning into different frequencies and reworking the piano using different tones.

I'm also interested in creating a portable setup. For example, I could use a table of 16 beer cans and make them shake with the same technology. That would be interesting, but I'm also interested in playing with other things.

I'm also working on a record of the piano installation. I recorded the installation in Amsterdam and Leuven using six microphones to capture different parts. The record will be released on the Edições CN label from Antwerp.

I like installations because once they're finished, they can tour on their own without me being there, giving them a life of their own. It's also good for me not to stick to the same thing. I've learned much about electromagnetic waves, computer coding, and piano string physicality. But I'm working on something different for the next project, like the robot or 16mm film. It's important not to become a specialist, I am somewhat against that.

To conclude, what trends do you observe in contemporary art and sound practices?

In 2011, I did my first tour in the US, and I had a suitcase with equipment that no one recognised at the time. People would come and look at it, curious about what it was. It wasn't guitar pedals but analog oscillators, which interested people. That trend continues, but conceptually, many things in the analog field have been explored, so it has become more of a collector's interest. I do not see many exciting new developments in analog technology.

However, I think we'll see interesting things from people who are just getting their first computer now. The younger generation, especially in places with less access to resources, can now learn everything on YouTube without going to university. I'm very curious to see how their work will evolve and how it will look and sound.

Another interesting trend is digital radio stations. I was involved with Radio Centraal in Antwerp, sometimes helping a friend with a programme. When I played in London, I had a session with NTS and noticed how popular these internet radio stations were. There is so much content to listen to, and that's something I'm also curious about.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.