Fraught, Feral, and Familial Neighbours:

The More-Than-Human Root System of “Antecâmara”

Part interview, part reflective essay, this text explores the root system of fraught, feral and familial neighbours beneath Luis Lecea Romera’s “Antecâmara”.

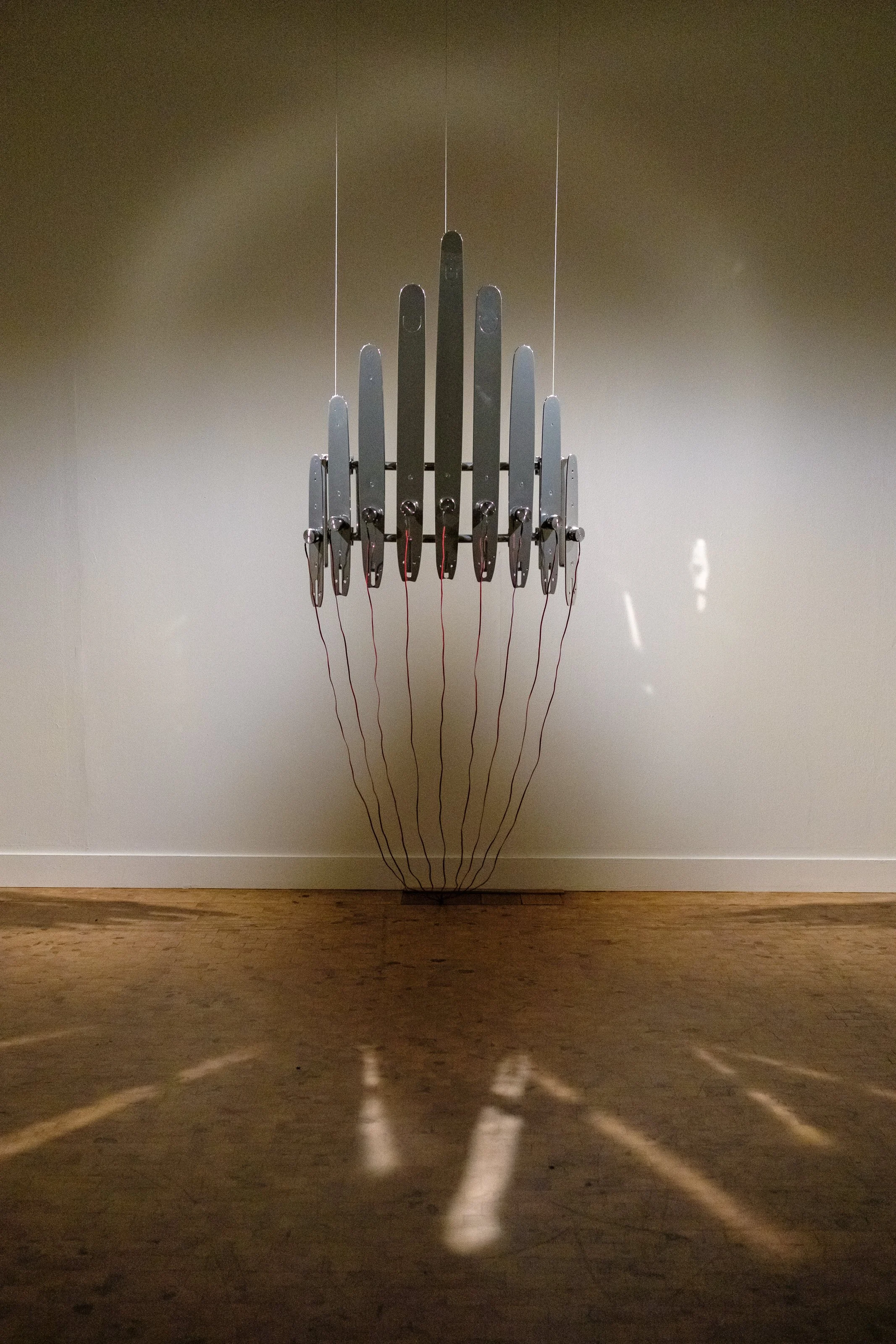

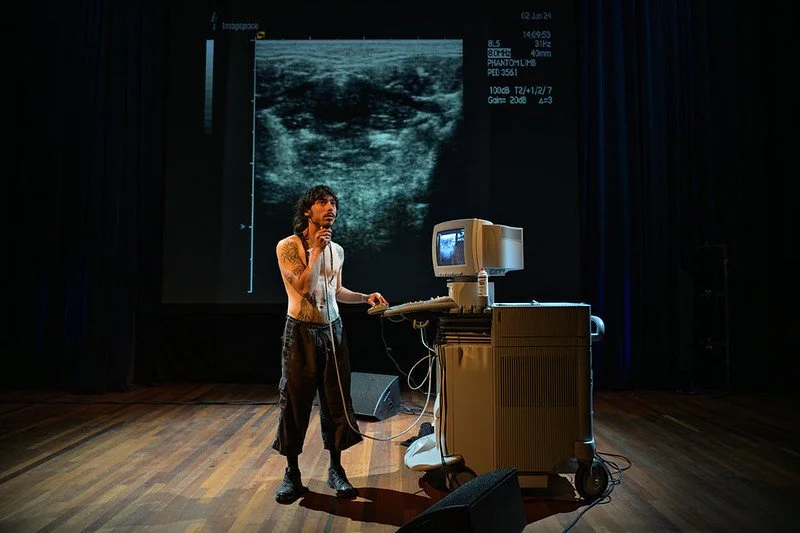

“Antecâmara”. Neighbouring Frequencies at FIBER Festival 2024. Photo credit: Alex Heuvink

What kind of stories do artworks tell about more-than-human relations? And if we think with those stories, what do they imply for how we live together with nonhuman species in our own urban contexts? In other words, how do we attune to other beings? Visiting FIBER’s Neighbouring Frequencies exhibition for the first time, I addressed these questions to Luis Lecea Romera’s work Antecâmara.

First Impressions

I found the installation in a small room at the end of a corridor in the exhibition space of de Brakke Grond, and decided to spend some time with it. The only object in the room consisted of nine gleaming metal plates, symmetrically arranged in a kind of triangle around the longest plate in the centre. A wire attached to each plate made them vibrate with sound: synth-like noises that would swell and recede in volume, underscored by trickling water, interrupted, at sparse intervals, by chimes of a bell. Ghostly overlayed frequencies invoked the discordant whistles of wind through an abandoned town; then again they reminded me of a soft voice, or a choir, singing. If I had to choose one word to describe it, I decided, it would be eerie.

Facing “Antecâmara”. Photo credit: Alex Heuvink (left) and Pieter Kers (right).

Reading the curatorial texts, I learned that the installation represents the troubled history of the eucalyptus tree on the border between Portugal and Spain, an area called A Raia (“The Strip“). We hear water trickling through the soil due to erosion, which is in turn the consequence of forest fires intensified by the widespread presence of the pyrophyte (fire-loving) eucalyptus. The metal plates are actually chainsaw guide bars, alluding to cross-border de-eucalyptising brigades who fight the tree using variously sized saws.

“It Helps You Breathe Better”

When I met Luis a couple of days later for an interview, my first question was: What is your earliest memory of a eucalyptus tree, and how has your relationship with it evolved since then?

He recalled: “It was in Madrid in the Retiro Park, the biggest, oldest park in the city centre. I remember seeing this huge tree as a kid with nothing around it except some dried leaves, and some of these aromatic seeds that are quite appreciated in the cosmetics industry. Eucalyptus is known for being a soothing ingredient, it helps you breathe better.”

Eucalyptus tree in Madrid. Credit: Riozujar on Wikimedia

Later, Luis’ perception of the tree deteriorated, or grew more nuanced: “I think that if you come from Spain or Portugal, you realise that this tree plays a role in the degradation of the landscape. When you say the word eucalyptus, there's a whole imaginary of wildfires, the plant’s overpopulation, speculation around it.”

Despite this cultural imaginary, debates around the presence of the plant rarely find their way into public discourse. It was only through FIBER’s RE:SOURCE residency in collaboration with the Portuguese festival Semibreve, situated at the borders of the Gerês-Xurés Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, that Luis began to intensively research the properties and histories of eucalyptus.

Histories of Empire and Capital

Native to Australia, eucalyptus is considered an Invasive Alien Species in Southern Europe. Luis walked me through the history of how this came to be: “The story of the presence of the eucalyptus tree in Southern Europe dates back to the 19th century when a missionary returned from Australia with a couple of seeds in his pocket. The plant started to spread, but it only really skyrocketed under governmental action, the dictatorial periods in Portugal and in Spain.”

He explained that the Spanish state instrumentalised the eucalyptus tree for two purposes: to dry out wetlands that fostered fears of malaria, and to fuel the paper industry. “After the civil war in Spain and the Fascist coup d’état, the triumphant Fascist government needed to rebuild a country to its liking: it needed to build the edifice of a bureaucratic state. And one of the first ingredients you need for that is paper.” The eucalyptus’ biological properties lent themselves to this endeavor: “It’s a very poor wood. It’s not resistant, not suitable for construction, but very useful for pulp making. And it grows insanely fast.” As regimes and interests changed, the plant's properties remained the same, and so today, its continued planting is ensured by the capitalist enterprises of now privatized paper companies. These corporations are known to approach small landowners and offer them hard-to-refuse sums of money for their eucalyptus wood. “Even if the villagers know that farming eucalyptus trees is dangerous for the environment and causes forest fires, they still do it. Not because they are not aware or they don’t have a desire to protect the land, but because it’s one of the few means of existence that they have.”

While this brief summary illustrates how the eucalyptus is deeply entangled in the colonial, Fascist, and capitalist histories and realities of the region, it paints the plant entirely as a pawn, tool, and even weapon wielded by protagonists. I would like to offer a possible re-interpretation: Could we not also understand the eucalyptus as something of an opportunistic actor in its own right, an ecology gone feral?

Feral Neighbour

Anna Tsing et al.’s Feral Atlas redefines the concept of ferality: rather than organisms escaping from domestication back into “wildness“, the Atlas’ feral ecologies are “ecologies that have been encouraged by human-built infrastructures, but which have developed and spread beyond human control.”[1]

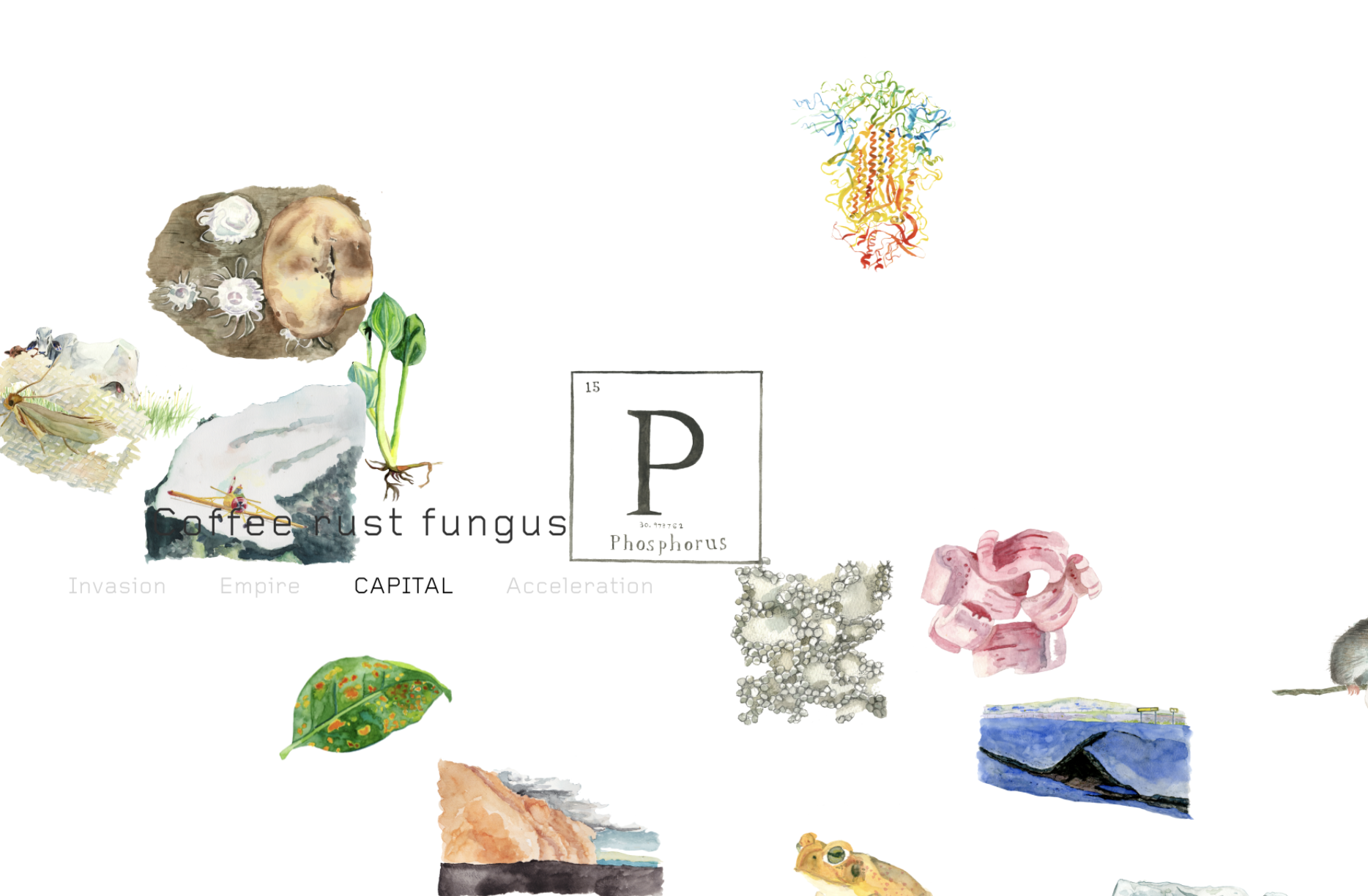

Human-built infrastructures, within the framework of the Atlas, are driven by the more abstract “infrastructure programs” of Invasion, Empire, Capital and Acceleration. Adapting to these programmes, nonhuman entities have started developing “feral qualities“: they are accelerated by climate change, creatures of conquest, like human disturbance, and thrive with the plantation condition.

Assemblage of Feral case studies. Screenshot from Feral Atlas: https://feralatlas.supdigital.org/ by Anna Tsing et al.

The eucalyptus tree in Spain and Portugal is not among the Atlas’ featured case studies, but I argue that it might well be: Its arrival and spread in Europe are connected to histories of human empires and conquest, its ongoing presence secured by the power of capital. Its usefulness for paper production lets it thrive under the plantation condition, its pyrophyte nature allows it to survive and even “like” the human disturbance of forest fires accelerated by climate change, and it materialises the ghostly legacy effects of two dictatorships.

Does all this make the eucalyptus tree not only a pawn, but also a player within this complex history? Some of Luis’ words seemed to echo these sentiments: “This tree is hard to eradicate, it’s still present somehow…it exists but it also insists on being present there.”

At other times he gently thwarted my plant-centric musings: “I don't know if this is a work about the eucalyptus tree or around the eucalyptus tree. I don't incorporate the literal matter, not even the sound of a eucalyptus itself. I'm not extracting a document from it, but following the aftermath of the presence of this tree.” He added that his work is not centred around ecology: “It’s more about exploitation and resistance to exploitation.”

Eucalyptus Re-Sprouting After Wildfire. Credit: Cabrils on Wikimedia

Composing Relations

What, then, are the implications of this work for living together with nonhuman species in our own urban contexts? I asked Luis what it means for a work so tied to a very specific ecosystem to be displayed in the isolated context of an exhibition room in the centre of Amsterdam. He explained that since he first started working with sound in his practice, his approach to both field recordings and site-specificity has become more flexible: “Years ago, the same way that I would not dare to modify or play around with field recordings, I also made some works where site-specificity was at the very core.

If we skip forward to where we are now, in 2024 here in Amsterdam, I feel that this element of site in my practice has mutated from site-specific to site-relational. I can make relations between locations, relations between sounds, spaces, species, without having to necessarily funnel everything into one particular location. This phenomenon of the eucalyptus tree is not tied to one coordinate in the map, but is something more abstract because it touches upon political systems and lineages all across the Iberian Peninsula. I am bringing a larger map of the whole region into one particular room here in Amsterdam.“

The Trouble Outside the Sanctuary

Nonetheless, these abstract concepts continue to manifest in ecological realities; there is no dividing line between ecology and human endeavours. What we hear in Antecâmara are sound artefacts from a landscape disturbed by human infrastructure projects, recorded not inside the Biosphere Reserve but often just outside its borders. “Funnily enough, I didn't even step into it,” Luis told me. “I was around it all the time because I was interested in what it protects itself from.“ The reserve is the only piece of land in the Iberian Peninsula where planting eucalyptus trees is prohibited by law. Eucalyptus’ presence, then, is the trouble just outside the sanctuary, the disturbance in its pre-chamber – Spanish: antecâmara.

This is where Luis gathered his field recordings: “The recordings that I picked up with geophones or contact microphones of the soil moving, water trickling, are taken on the edges of the reserve, in spaces that are not possible inside of it.“ He refers not only to the eucalyptus: “Because it's a very mountainous region, there are a lot of wind turbines. I plugged geophones onto wind turbines that were on the perimeter of the reserve. Instead of going into this natural paradise and recording the peaceful wind or the peaceful watery spring, I was interested in recording the same earth and the same wind, but through all of the different media and bodies that were adjacent to the reserve.” What we hear is never the rustling of eucalyptus leaves, but the trickling of water due to soil erosion and the swishing of wind turbines. What we don’t hear are the sounds of flourishing local fauna and flora; there is no birdsong. This soundscape is the aftermath of the presence of a plant shaped by and shaping harmful systems. The eucalyptus is able to make a living among capitalist ruins[2], which are in turn built on Fascist and colonial ruins.

Neighbourhood as Methodology

Indeed, it is in layers of fraught and familial neighbourly relations that the story of this work unfolds. One field of neighbourly tension exists between the protected natural reserve and the patches of degraded landscapes dotted around it. Another layer of neighbours, which Luis stressed very fondly, was the network of inhabitants of the rural valley Serra da Cabreira, which influenced the way the residency unfolded: “I think that from the first minute, I understood that this was also a project that was going to grow and become feasible through interpersonal relationships, rather than larger abstract structures.”

Luis and his friend and fellow artist Kyulim Kim found their sites for filming and field recording with the help of Rafael, the director of Semibreve, who referred them to family, friends, and friends of friends. “I think it was like the right way for this project, to also mimic how things work in this valley as my methodology. We really didn't know where we were going to film or where I was going to do the recordings until we were there.” At one point, this network of neighbours physically dragged the artists out of the mud: “We got stuck in the mountains and in this word of mouth, like a villager friend of a friend of a friend came to rescue us in the dark in the rain. That was part of the residency too.”

Resistance Against Persistent Ghosts

Another very important layer of neighbours in this work is the relation between the countries of Spain and Portugal and the cross-border resistance spawned by the eucalyptus tree: de-eucalyptusing brigades. Luis explained “They operate as guerrillas: basically, they go around the hills and the forests armed with chainsaws, with the aim of eradicating the presence of these trees. They have very sophisticated techniques, because it’s not only about chopping the trunk — sometimes they make a sharp incision with smaller blades and insert a specific species of fungi close to the root.”

Luis’ use of chainsaw blades as the material for his installation references these practices. “I see them as an act of resistance against the ghosts and legacies of the dictatorship that persist in the environment.” The tree both symbolises and materialises these “ghosts” of the past: “We think that we chopped them, but it’s really not true, the roots are there and they keep on re-sprouting. I insist on making allusions to these guerrillas, because they’re comprised of people from both sides of the border. There’s a shared problem, but they can not go vertically to ask for responsibility, to the governments that are pressured by the paper industry lobby in both countries, so they act horizontally.”

De-eucalyptising neighbours at work. Credit: Nacho Jorganes

Singing Saws

When I first learned that the installation was constructed out of chainsaw parts, this choice struck me as quite a violent one. Talking to Luis helped me understand the complex socio-ecological stories behind it, but it was only later that I realised the material actually subverts the violence it implies: In Antecâmara, the eucalyptus’ context is instrumentalised once again, but this time literally. It is made into an instrument, allowed to communicate subtly, sonically, so that we may listen, pause, consider.

“It is easier to tell stories of communal triumph over adversity. Can we also learn to tell stories of environments gone wrong?”, the Feral Atlas queries. “In times of environmental catastrophe, can we make common cause against the destruction by attending to its fine details?”[3] “Antecâmara” confronts us not with cutting, but with singing saws, and they sing a complicated story.

Whether or not the visitors wanted to engage with this particular story was up to them. I asked Luis about storytelling in his work: “It’s nice to have the backdrop story of everything, but I don't necessarily demand from the audience that they know all of it. The work should be autonomous in the sense that it affects you in a way. I think that there's a tendency lately in the arts, particularly in media art that touches upon the environment, that we demand from an artwork to do some sort of intellectual heavy lifting. I don't think that’s fair, firstly for the artwork and secondly for the audience.”

Listening to “Antecâmara”, FIBER Festival. Photo credit: Alex Heuvink

From Root to Crown

The root systems and relations of an artwork matter: Antecâmara’s story attunes curious audience members to fraught, feral, and familial neighbourly entanglements, which translate into our own urban contexts. Complex human and nonhuman travel stories interweave in cities, novel ecosystems emerge and ways of co-existing are being trialled and tested in ongoing practice.

Amsterdam, much like A Raia, has its fair share of ghosts and guests, human and plant, and much to gain from listening. When I told Luis about the 8 million euro budget allocated by the municipality of Amsterdam to combat the “exotic invasive” plant Japanese Knotweed, transported to the Netherlands by the explorer and botanist Phillip Franz von Siebold in the 19th century, he was immediately intrigued: “Cool! So it’s a plant that can damage architecture?”

The root system of Japanese Knotweed is able to grow through paving, tarmac, building foundations and flood defences, and finding Knotweed on or near your property drastically reduces real estate value. “Maybe we should spread it around Amsterdam to solve the housing crisis”, Luis suggested. At the same time, the plant is edible and appreciated for its healing properties in traditional East Asian medicine, similar to the eucalyptus’ use in Indigenous Australian medicine – “It helps you breathe better”. It is by no means my intention to downplay the eucalyptus role in wildfires and the loss of life and landscape degradation that comes with them. Instead, the singing saws helped me understand that it might be worth getting to know one’s complicated new neighbours. Knotweed, like eucalyptus, is a fraught and feral neighbour, and despite best efforts it isn’t going anywhere. Artistic practices creates space to listen and reflect critically: How, then, do we want to go on living with these plants inside our cities?

The root system matters, but the stem and crown of an artwork hold a different kind of power: Listening to the howling and trickling soundscape of Antecâmara unprompted by curatorial texts creates a completely open space for associations. We can still hear the saws sing an ecosystem: wind, water, ghosts – but we might as well imagine a landscape closer to home, a future Amsterdam turned eerie Atlantis.

Notes

[1] Anna Tsing. 2021. “Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene.” Feralatlas.org. 2021. https://feralatlas.org/.

[2] Anna Tsing. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press.

[3] Anna Tsing. 2021. “Feral Atlas: What is the Anthropocene?.” Feralatlas.org. 2021. https://feralatlas.supdigital.org/?cd=true&bdtext=what-is-the-anthropocene

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetry, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.