“Dark Souls”: An Exercise in Rhythm and Moving Otherwise

This text dives into a video-game called Dark Souls, it explores the relation that the game develops between rhythms and bodies, whether digital or physical, and the blurring of the limits of those same bodies.

Screenshot from the game’s safe hub: Firelink Shrine, Dark Souls: Remastered (2018), FromSoftware.

“In the Age of Ancients the world was unformed, shrouded by fog. A land of gray crags, Archtrees and Everlasting Dragons. But then there was Fire and with fire came disparity. Heat and cold, life and death, and of course, light and dark.

[...]

The Darksign brands the Undead. And in this land, the Undead are corralled and led to the north, where they are locked away, to await the end of the world... This is your fate.”[1]

***

Right after the opening of the game, you find your character locked in a cell. At that moment an unknown knight pushes a dead body in your cell from a big hole in the ceiling that you can’t access. On this body is a key that will open the door of your cell and allow you to start your journey in the lands of Lordran where you will fight witches, lords, dragons, and kings…

Screenshot from the game’s opening, Dark Souls: Remastered (2018), FromSoftware.

Dark Souls is a Japanese action role-playing game[2] developed by the studio FromSoftware and directed by Hidetaka Miyazaki. The entirety of the game takes place from a third-person perspective, meaning you see the character you control rather than view the world through its eyes. By collecting items and reading their description, exploring new areas, interacting with the very few and obscure characters that you’ll meet in the corner of a building, you puzzle back together the story of the places you’re stepping into, as well as the purpose and meaning of your fate as an Undead.

Walking from the Firelink Shrine to the Depths, through Blighttown to Sen’s Fortress and Anor Londo (only to name a few), all this will be done through the body and physics of your character. During this time you have to learn how to move your character, understanding how much stamina it costs you to attack, parry or roll, making sure that you don’t run out. Rolling is one of the main and most important mechanics of the game because if you time your roll at the same time as the enemy's attack, you will not take any damage even if it is going through you. You will invest hours in calculating the weight of the equipment you carry so that it is not too heavy for your character and that it can still move as fast and fluidly as it usually does. This amongst other details creates a porosity between the player and its character.

Screenshot from the game’s opening, Dark Souls: Remastered (2018), FromSoftware.

That movement, however, is not isolated. It takes place within the digital environment that you explore, it is a movement in relation. Enemies scattered all around the different zones reappear everytime you die or go to a safe spot identified as “bonfires” in the Dark Souls series. Therefore when you die (which you do a lot[3]) and when you want to go back to explore, you have to fight the same enemies that populate the area that you’re moving through. All of those enemies function in quite a similar way as your character does: the algorithm is basic, with each enemy following distincts attack patterns. By repeatedly facing them, the player must learn and understand their movements and rhythms, they become the referents that trigger your movements.

Those notions of movement and rhythm are key in playing Dark Souls and are some of the most interesting in-game mechanics of this game. In his introduction to Henri Lefebvre’s book Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life, Stuart Elden defines Lefebvre’s concept of rhythm as “[...] something inseparable from understandings of time, in particular repetition. It is found in the workings of our towns and cities, in urban life and movement through space.”[4] The book draws a philosophy on rhythms, their differences, origins and meanings. It also outlines a method to listen to those rhythms. Even if Lefebvre's perspective is specifically oriented towards the urban space, rhythms have been present, theorised and used in a lot of other fields.[5] In this sense, Dark Souls presents a lot of parallels with Lefebvre’s understanding of rhythms and offers an exercise in rhythm, challenging the player’s (the rhythmanalyst’s) understanding of its own body and movements. It makes its taught nature and its relationality to other beings explicit but also offers a way out in its freedom to build your character to your wishes.

I - Move Through

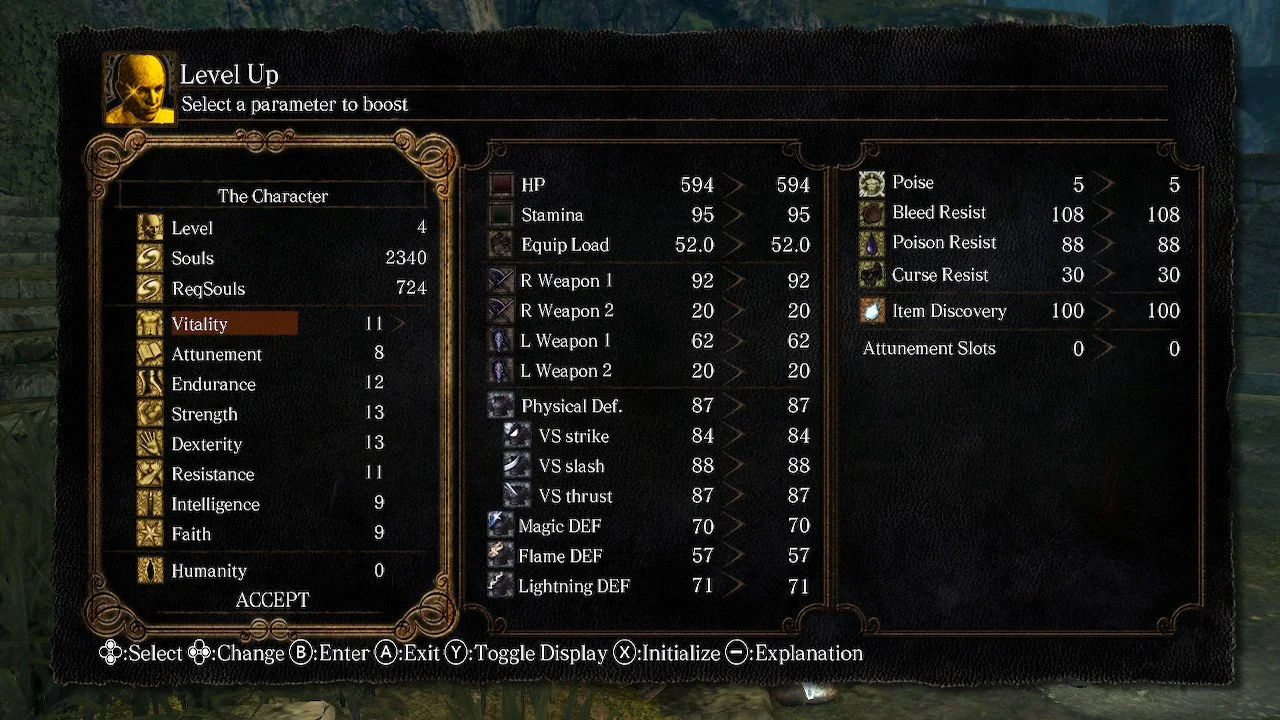

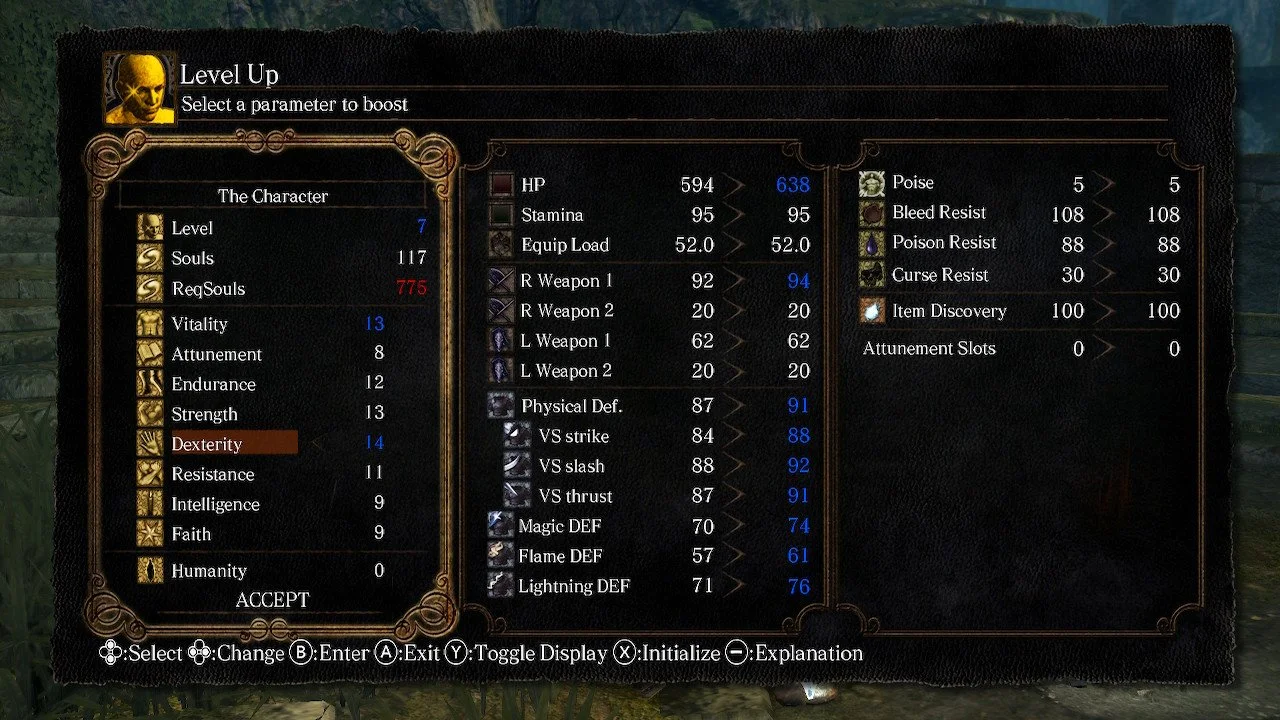

Before starting the game you have to create your character. The menu offers different classes from which to choose, such as warrior, knight, pyromancer, sorcerer, thief, cleric, wanderer, amongst others. These classes represent the starting stats and equipment of your character. You can also change the physical appearance of your character but no matter what your character looks like, it is the stats that will influence the way your character moves. Those stats are quite complex and obscure in the first place. There is Vitality (your health), Attunement, Endurance (your stamina), Strength and Dexterity (to be able to use different weapons), Resistance, Intelligence (to use magic) and Faith (to use miracles).

Screenshot from the character creation menu, Dark Souls: Remastered (2018), FromSoftware.

Although the choice of class you make in the beginning is important, you will, throughout the game, be able to upgrade those abilities to specialise your character in a certain combat style. For example if you build a thief you will most commonly not have a lot of Vitality but will be able to roll and dodge attacks a lot and attack quickly. If you build a sorcerer you will use magic therefore making you quite weak but you fight from a long distance from enemies, if you build a warrior you will most likely carry big weapons, have a lot of life but you will attack very slowly and close to enemies. There are a lot of ways that your character can move: it can go fast or slow, be played from a distance or close. Depending on the character you build, its move set will change.

Dark Souls’ stat system is quite rigorous. If you lack a point in Endurance, your character might not be able to carry a certain weapon. Exceeding the weight limit (defined by your stat of Endurance) drastically impacts your character’s movements, making rolls and attacks heavy and slow, giving enemies more time to attack you as you recover. Tapping into its RPG roots, Dark Souls limits the number of consecutive attacks or rolls you can perform. Once you use all your stamina you have to wait a few seconds for it to recharge. However, in a fight, if you attack once too much thinking you were about to fell the enemy, and then find yourself with no stamina, you only can helplessly watch as the enemy attacks and kills you, with no way to dodge, run, or fight back. Through endless trials, the player learns to master the character’s movements, its patterns: speed, attacks, weapon range and more.

Screenshots from the character amelioration menu, Dark Souls: Remastered (2018), FromSoftware.

Compared to other games where the character moves at the player’s will, Dark Souls inverts this process. The character has its own weight, it moves at its pace and rhythm and there’s more or less nothing the player can do about it except upgrade certain skills and abilities. It is not simply a vessel for the player to move through but also a body that has its own physicality in this digital realm. The player has to listen to those different rhythms and to shift the way they play from a player moving as a digital body to a player moving through a digital body. Dark Souls offers an understanding that goes beyond the representative aspect of the avatar. This is why I call this persona “the character” and not “the avatar”. Even if it can resemble or represent the player[6], it still has its own way of moving, its own rhythm. It is not your character that resembles you but the opposite, you need to learn the pattern and the speed at which it moves. You have to learn to move all over again, learn how to be in another body, in a digital body.

II - Move With

Lordran is filled with monsters, creatures, and ruined knights that you will fight again and again to make your way through those desolate lands. Their coding is very similar to yours in the sense that they too have patterns and rhythms that, through repetition, you learn to understand and read through. The algorithm of these enemies is quite rough and simple compared to other video games where the algorithms are really “smart”.[7] In Dark Souls, the enemies often have a set of a few attacks that they will use against you, however they will always be the same but not always in the same order. Through different placement towards the enemy or movements that you do, it will trigger certain patterns. Some people in the speedrun community[8] use this to do something called “scripting”: basically they move a very specific way to trigger the bosses exactly as they want them to move to kill them the most quickly.[9]

Learning the patterns of the bosses and the enemies is a key point to navigating Dark Souls. Because dodging is so important, you have to be able to understand that the way this enemy lifts its weapon means it's going to attack from the left to the right, if it starts to take a step back then it means it's going to dash really quickly to try and impale you. Those rhythms and patterns are the metronome to your movements. They dictate when you should roll back, when you should lift your shield or take a second to heal yourself. But as we can see, this rhythm is in constant tension with another rhythm : the one of your character. Even if you know the rhythm of your character, enemies teach you how to use this rhythm and how to apply it to fight. Moving your own character is the first step but you will truly learn to move it by moving with enemies. Moving in Dark Souls is not lonely but populated, it asks the player to learn how other beings move their body to move its own.

In his text, Lefebvre makes a distinction between cyclical rhythms and linear rhythms: “ The cyclical originates in the cosmic, in nature; days, nights, seasons, the waves and tides of the sea, monthly cycles, etc. The linear would come rather from social practice, therefore from human activity: the monotony of actions and of movements, imposed structures.”[10] To Lefebvre, linear rhythms are not intrinsic to humans: “Gestures cannot be attributed to nature. [...] These gestures, these manners, are acquired, are learned.”[11] He then writes: “Humans break themselves in [se dressent] like animals. They learn to hold themselves. Dressage can go a long way: as far as breathing, movements, sex. It bases itself on repetition.”[12] Enemies are the ones teaching you this rhythm, they teach you how to move and how to use those movements. To beat an enemy you have to know it, know its rhythm. Trial, after trial, you end up spending hours facing one boss and you develop a relationship with it through rhythm. You start counting: wait, one, two, three, dodge; one attack, two attacks, roll back; parry, attack, one, two, dodge, one, two, dodge…

III - Move Beyond

We first saw that the player had to learn how to move in a new body, understand the rhythm and physicality of this digital body compared to their own physical body. Then in a second time this digital body is itself put in tension with new rhythms: the ones of enemies. During the entirety of the game, this creates a relationality, through rhythm — of the player’s own bodies (digital and physical) and other bodies (whether its enemies or the architecture)...

The experience of playing Dark Souls introduces you to a negotiation between the different rhythms present in the game: the player’s, the character’s and the enemies’. This negotiation brings a lot of questions through its gameplay: Do you move a certain way because of your character’s set of moves? Because you move in relation to the enemies or because you try to mirror your own physical rhythm to the character’s rhythm? In that small interstice, the rhythms, their meaning and the bodies that they constitute find themselves entangled.

Galloway, in Gaming : Essays On Algorithmic Cultures writes: “The activity of gaming, which, as I’ve stressed over and over, only ever comes into being when the game is actually played, is an undivided act wherein meaning and doing transpire in the same gamic gesture.” When playing the game, you're compelled to understand how it dictates your movement. In this movement and its taught nature the doing and the meaning come together. The game puts you through dressage and teaches you the set of rules tying together the spatiality and physicality of this kingdom. In its own way, Dark Souls reproduces the same patterns that are imposed on our bodies. Even if the set of rules that regulate movements is quite different, the process is similar in its method.

However, as we have seen in the beginning, the way your character moves and the way you play it can differ a lot in-between players. The enemies rhythm can not change, but yours radically can depending on the weapons you carry, how you upgrade your character, and what kind of armour you wear. Because of its almost non-exhaustive number of combinations of armours, one-hand sword, two-hands sword, spires, katanas, halberds, shields, spells, pyromancy, miracles, etc, there are as many gameplay styles as there are players. This is where Dark Souls offers a means of moving otherwise: in the freedom that it gives to its players. Each player creates their own way of moving to the dressage of rhythms, of understanding it. It allows one to create a unique positionality towards those rhythms and to choose how they wish to deal with them. Through moving otherwise, the player, while engaging with disciplinary powers, resists and plays with them, subverting the power they hold.

Notes

[1] Dark Souls Wiki, Opening, https://darksouls.fandom.com/wiki/Opening_(Dark_Souls) (accessed 31 July 2024).

[2] We will shorten this to Action-RPG or RPG depending on what aspect of the game we’re discussing.

[3] To reinforce the idea that dying is really a core mechanic of the game, the second edition of the game, released in 2011, with added downloadable content from the developers was called Dark Souls: Prepare To Die Edition.

[4] Elden, Stuart. “Rythmanalysis: An Introduction.” Introduction to Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life by Henri Lefebvre (BLOOMSBURY CONTINUUM UK, 2004).

[5] Lyon, Dawn. What is Rhythmanalysis? "What is?" Research Methods Series. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. (3)

[6] Some players decide to make the character they play look like them but others create really odd looking characters or ones that just don’t look like them.

[7] AI and Games, Analysing the AI of The Last of Us Part II | AI and Games #70 https://youtu.be/BghECmeLda0?si=_sGd1-udvyZUe5RV (accessed on August 1st 2024).

[8] Speedrunning is “the activity of trying to complete computer games, or parts of computer games, as quickly as possible, especially by taking advantage of any glitches”, Cambridge Dictionnary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/fr/dictionnaire/anglais/speedrunning (accessed on August 1st 2024).

[9] QueueKyoo, Dark Souls - Any% Speedrun - 20:23 (World Record) https://youtu.be/ogemypIquNo?si=Thn8qbWKcsKcQcUW

You can see an example of scripting at 06:45, he throws a firebomb at the exact place where the boss will appear so that it takes damage right after the cutscene.

[10] Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space,Time and Everyday Life (BLOOMSBURY CONTINUUM UK, 2004).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Alexander R. Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Sources

Galloway, Alexander R. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Armitage, Dylan. Sonic Spaces in Dark Souls - First Person Scholar. First Person Scholar - Weekly critical essays, commentaries, and book reviews on games, September 18, 2020. http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/sonic-spaces-in-dark-souls/

Jørgensen, Kristine. On Transdiegetic Sounds in Computer Games. Northern Lights: Film and Media Studies Yearbook 5, no. 1 (September 2007): 105-117. Intellect Press.

Lefebvre, Henri. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore. London: Continuum, 2004. Originally published as Éléments de rythmanalyse by Éditions Syllepse, Paris, 1992.

Ivanchikova, Alla. On Henri Lefebvre, Queer Temporality and Rhythm. Journal for Politics, Gender, and Culture, vol. 5, season-04 2006.

Lyon, Dawn. What is Rhythmanalysis? "What is?" Research Methods Series. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Shinkle, Eugénie. Video Games, Emotion and the Six Senses. University of Westminster, London, UK, 2008.

Read more

ABOUT THINKING BODIES

Thinking Bodies was conceptualised as an effort to build an exploratory body of knowledge(s), that draws upon the festival’s theme and weaves together perspectives, writing styles and formats. Drawing from the theme of the FIBER Festival 2024 edition, Outer/Body, we invited aspiring and emerging writers from a multiplicity of backgrounds to share their contributions, ranging from essays to interviews to poetries, resulting in a rich archive of knowledge.